Mélange

Unnamed lake, Eastern Sierra, CA

View from the summit of Alta Peak, western Sierra Nevada

General Sherman, the world's largest tree

Shasta winter summit bivouac

A late spring trip to the Eastern Sierra:

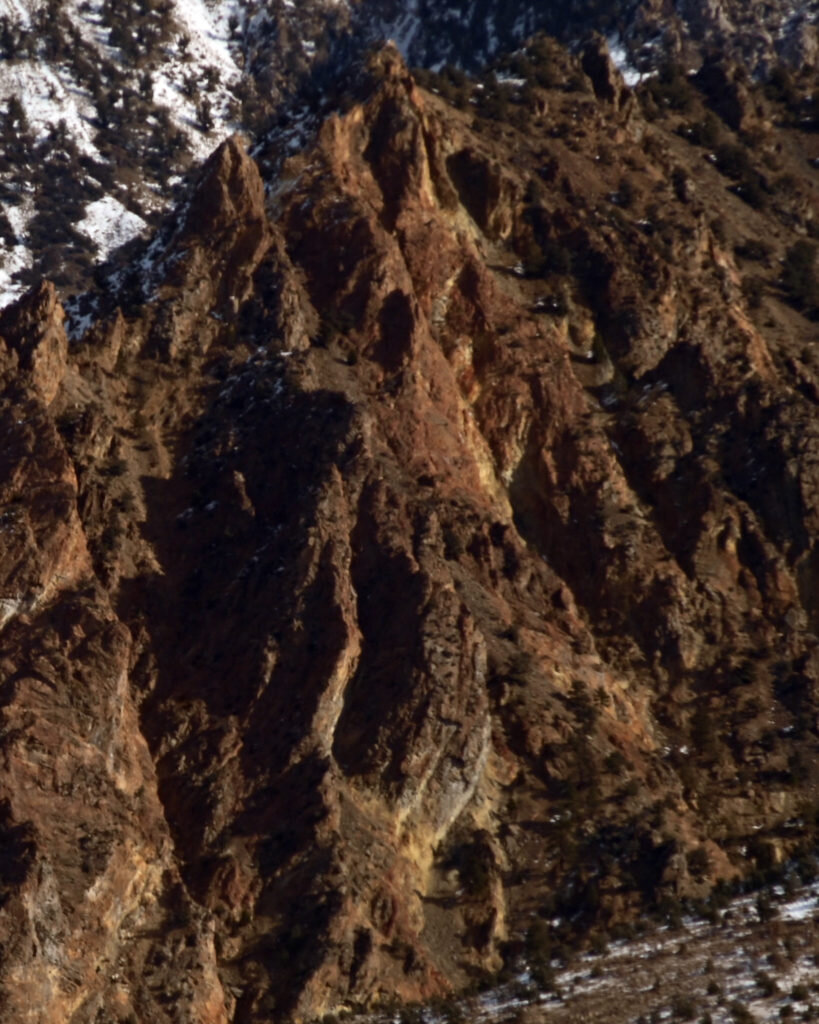

Red Slate Mtn

Banner Peak, my objective for the day

A road trip to Oregon and climb of Mt Hood:

Walter likes camping

Michelle's car camping spread!

Walter meets a marmot!

A 40-mile, 13,500 ft elevation gain dayclimb of remote Mt. Kaweah:

Rodent-proofing in Mineral King

Gorgeous Spring Lake

Big Five Lakes

LeConte, Corcoran and Langley

Russell and Whitney

Last view of the Kaweahs

Summit to Sea Microadventure

I've long been inspired by Alastair Humphreys and his brand of "microadventures." There's just so much freedom and enjoyment to be had close to home. What better time to try this new style than mid-quarantine?

My mission was elegant: Make it to the Pacific coast and back. My rules were simple: Leave from home. Take as little as possible. Maximize trail and off-trail terrain while minimizing road. Travel as fast as possible by foot.

The result was a fantastic little adventure. Definitely more "character-building" than fun at some points. But overall it was beautiful, liberating and an immersive escape from our predicament. Hope you're all doing well!

Suburban assault microadventure from Hari Mix on Vimeo.

Top 10 social distancing moments of the decade

Boredom presents a very real, if insidious, peril. To quote Blaine Harden from the Washington Post: "Boredom kills, and those it does not kill, it cripples, and those it does not cripple, it bleeds like a leech, leaving its victims pale, insipid, and brooding...Rats kept in comfortable isolation quickly become jumpy, irritable, and aggressive. Their bodies twitch, their tails grow scaly."

Jon Krakauer, "On Being Tentbound," Eiger Dreams

Growing up, I would read and re-read mountain literature. One piece that has always stuck with me is Jon Krakauer's "On Being Tentbound," which describes the all too common ordeal of being stuck in a tent in bad weather while on expedition. I've been tentbound on numerous occasions and always smirked as I know this is what Krakauer warned me I'd signed up for.

How's it going for me these days? Not particularly well. But I'm enjoying leaning into being tentbound and sort of embracing the suffering. That's one part of mountain trips I genuinely enjoy: acknowledging when things are getting tough.

So, in this moment of reflection, I figure I'd share the ten most socially-distanced moments of the last decade. Starting with...

10. Camping alone on the summit of Shasta, winter.

Just before the pandemic really got going and shelter in place orders went into effect, I traveled to Mount Shasta and bivouacked on the summit. The stars were unbelievable.

9. Little Switzerland

In 2014, Brad Lipovsky and I traveled to the Pika Glacier in Denali National Park. A ski plane dropped us off and picked us up 9 days later. In the Alaskan summer, it was light 24 hours a day, so we became nocturnal and climbed beautiful granite lines by night. The feeling of remoteness was palpable...except when the planes landed each day for tourist photo ops.

8. The Absarokas

The Absarokas are one of Wyoming's wild ranges, seeing much less attention than the nearby Tetons or Wind Rivers. I helped teach a field course there several Septembers and we had wild experiences each time. Perhaps the craziest was when grizzlies came into camp and pawed under the vestibules of several tents!

7. Jarbidge

Where's the furthest from a paved road in the lower 48? Jarbidge, NV. On the three-hour drive north from Elko, we ran into an absolutely apocalyptic Mormon cricket plague. The roads were slick from their corpses, and the others cannibalized in the tire tracks. Camping in an environment where the entire ground was moving (and crunching!) underfoot was an absolute nightmare. EWWWWWW!

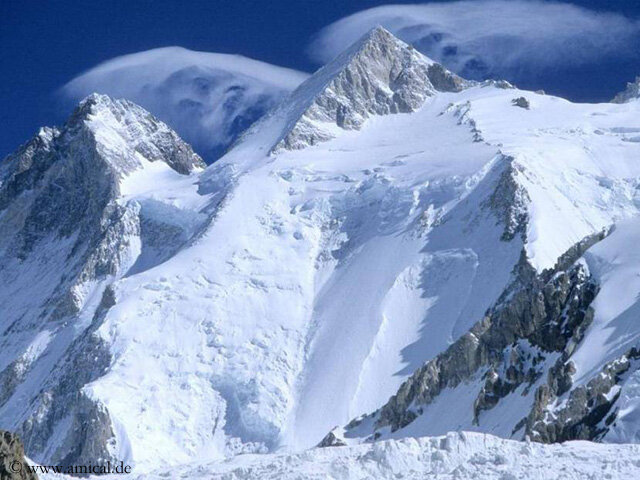

6. Gasherbrum II

On the summit of the world's 13th highest mountain, I felt alone. OK, technically, I was with people. Pasang and Mingma Gyalje. But that was it. And it was a storm. Rappelling down on the border of China and Pakistan I knew we had to get everything right if we wanted to see people again.

5. The Pamir

Tajikistan is the world's 3rd or 4th least visited country at just 4000 visitors per year. And hardly any of them come over the Karamyk pass, formally closed to foreigners. Fortunately, my handlers had pre-bribed the military with cigarettes. And I can assure you none of them are alpinists...the customs officers laughed at our tourist visas.

4. The Whites

The wildest, most remote and longest stretch of tundra in the lower 48 belongs to the White Mountains of California and Nevada. I learned just how far they were from civilization when I was caught in a ferocious windstorm during November, 2014.

3. The Inylchek

In 2015, I walked alone up one of the world's greatest glaciers, the Southern Inylchek in Kyrgystan into the heart of the Tian Shan. Even though I broke my toe on day one, I had a wonderful and life-changing trip. This is as good and as wild as big mountains get. And the rivers draining them...forget about it.

2. Rolwaling

How profoundly wild is Rolwaling? Just look at the header of this site...I'm ascending the final few meters to the foresummit of unclimbed Langdung. Within sight of Everest but receiving only a fraction of the attention, Rolwaling is a stunningly beautiful valley with wonderful people. But in order to get there, you'll have to earn it, as the road ends down low in the rainforest.

1. The Gobi

I'm heavily biased towards the mountains, so this is high praise. I've never felt more vastness, more small, than when I crossed Mongolia's Gobi desert in 2012. Not only is Mongolia the world's least populated country to begin with, but the inhospitable landscape in the southern part of the country is incomparably remote. We drove for four days without seeing anyone, navigating only by GPS and sometimes covering just 5km in an hour. It felt like being out at sea. Did I mention we found multiple dinosaurs?

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going.

No feeling is final.

Rainer Maria Rilke

Solstice

Once again, I found myself checking the White Mountains weather forecasts. They looked mediocre...a bit of wind near the summit but probably not too much. About two days before a storm. And once again, I decided to head up into the unknown, the only difference being that this month's attempt on Boundary Peak, the highest point in Nevada and the proposed end point of my Thanksgiving traverse, would be a simple dayclimb with an easy retreat should things deteriorate.

The climb was enjoyable. Cold and gray, but unbelievably quiet and peaceful. Solitude on the solstice.

Again, two bighorn sheep greeted me near the White Mountain crest. They paused, acknowledged me, then gracefully traversed over the ridge into California.

The wind picked up quite a lot near the summit, so it was not the day for a summit lunch break. But I did have the opportunity to look all the way southward across the White Mountain traverse to see the landscape where I was caught, overpowered, and humbled a few weeks ago. It was an emotional experience to interact with this landscape once again.

Loose ends

I've come out of the Thanksgiving experience. The psychological trauma has passed. New memories and details have emerged. For example, I remember during my downclimb from the ridge being so dehydrated that my vision was quite blurry. And while climbing just 100 feet above the creek, I pressed my lips to a moist streak on the rock wall to see if I could get some moisture. I remember thinking that I wasn't sure if I'd be able to complete the downclimb or have the strength to reascend back to the ridge. I found this lower section on Google Earth:

A few more details to share...

Paul, my driver, revisited the area to take photos of the scene during good daylight.

Mono County Search and Rescue posted their mission report from the incident. It was eye opening. I knew they had a rough time, but I didn't know a rescuer had been injured (by rockfall) looking for me. I'm quite saddened, but not surprised...in many ways it was a blessing being alone on such dangerous and unstable terrain. One photo tells more of the story than I ever could:

My whole life I've been searching for mastery. I've always found it most interesting and most rewarding to dig deeply into my passions, from yoyos and other skill toys, to earth science, running and alpinism. In many of these cases, I reached a high level of proficiency, but often felt like I left a few rungs on the ladder.

The White Mountains self-rescue was the one moment in my life where I actually realized my full potential. On a physical level, it required more calculated execution than my finest race ever in track. From a mental focus perspective, it was significantly harder than descending the world's 13th highest mountain without, food, water, oxygen or the ability to clearly see this summer. And in terms of problem solving, nothing in my life has ever presented a bigger, more complex set of challenges, including my PhD qualifying exams. For thirty hours, I was perfect. But it doesn't feel an accomplishment, just a singular moment of intensity.

I will become even more adventurous in the future. As I build more stability in my professional, financial and personal life, it will become increasingly important to add risk rather than retreat into security. Mountains are just a canvas for my fullest expression.

Thankful to be here

"No matter how powerful the illusion, you are never in charge"

Me

This is how it begins

1. You’re outside over a day away from another human. Ok,technically, you’re over 13,000 ft on the longest, most remote and highestcontinuous ridgeline in the lower 48…the White Mountains of CA/NV. You’re overtwice the height of the Grand Canyon above safety. But the mountain superlativesare almost irrelevant because…

2. You’re hit with an unforecasted extreme wind event with confirmed gusts over 100 mph. That’s equivalent to at least a category 2 but likely category 3 hurricane. Except…

3. Air temperature is about five degrees Farenheit. Much more detail of the storm and the damage it caused in the valleys will be discussed below. But for now…

Got any ideas? Great! Let me rule them all out for you:

Pitch a tent/bundle up/hunker down. All of these are not even worth considering. The wind was lifting me airborne and blowing me over (160lbs + 40lb pack). Pitching a tent would be extremely challenging in winds 1/3 this powerful. Even if a tent were already pitched it would be immediately shredded. So, no, you cannot make a shelter, no you cannot light a stove (to melt snow for water) and no you can’t even bundle up with those extra jackets in your pack. If you take your pack off and let go of it for any reason, you will likely watch it get blown into Nevada. It is too windy to access anything in your pack. And of course, wind chill is off the charts. If you stop moving for any reason you’re not gonna make it. Oh, and by the way, a storm is coming tomorrow at nightfall and is expected to drop five feet of snow. If you don’t have a plan to get completely back to civilization in the next 36 hours that’s it.

Get rescued. How? No human could reach you, and a helicopter…are you kidding? Heli rescues are not possible in winds even half this powerful.

Find the best way down. Great idea! There are noroutes off the ridge from where you are. It is too windy to read a map. Thewind creates a ground blizzard effect where windblown snow and ice make it notworth its while. I made several attempts to evaluate multiple routes down butwas unable to do so. There are 4 directions to travel:

Forward:This would be the best option over 95% of the time. But it’s over 21 miles ofridgeline to the car. Unless the wind dies down, you probably won’t make it morethan another couple hours on the ridge.

Backward/reversethe route: There is a technical, exposed section of ridgeline that preventsthis. This was extremely delicate rock climbing the day before and you’dunquestionably get blown off. Also, even if this were possible, this is for theprivilege of having to re-ascend the third highest peak in California, White MountainPeak, likely with significantly higher winds.

Bail east into Nevada: One look down this way and you realize it’s a horror show. Geologically, the Whites are bounded by a normal fault on the West, meaning that the east side is the “dip slope” which is less steep but muuuch longer. Plus, then you’re descending into Fish Lake Valley (coincidentally where I did much of my PhD work). It’s extremely remote, without infrastructure or resources outside of the tiny outpost of Dyer, NV.

Bail west into California: First of all, its hard to even glance into the wind. So it’s hard to tell, but you’re next to the start of a ridge that is very easy at the top but it’s quite obvious that it would be a horror show. No one in their right mind would do this. On the upside, there are lots of resources, communications, search and rescue in CA.

Your move.

The vision

Traversing the White Mountains is one of the most unique adventures one can find. Their remoteness, the starkness of the tundra landscape and the beauty of the Sierra and other adjacent ranges make this trip an experience to remember. Add the ancient Bristlecone Pines, the oldest living things on Earth at over 4000 years, and you truly gain an appreciation for our relationship with the natural world. But you'll have to earn it. Traverses are done only by several parties each summer, and teams often take up to five days. The trip is seldom done in the other seasons. I'm only aware of two wintertime traverses, the first being done by Eastern Sierra legends Jay Jensen, George Miller, Galen Rowell and Dave Sharp on a National Geographic sponsored expedition in February 1974. Unlike my trip, this adventure was in the heart of winter and traversed the entire range and done on skis. The team took 16 days and encountered serious storms, including one with 100+ mph winds that trapped them for five days. Ironically, National Geographic decided not to run the article because of "lack of life-threatening circumstances!"

"For me, seeing the stark beauty and remoteness of the range in winter, with constant views of the snowy Sierra as if from an aircraft, rivals any mountain experience I've had in the greater ranges of the world"

Galen Rowell

I've dreamt of the White Mountains traverse for about a decade and only this fall did I start to think it could work. Not only did I need the requisite fitness, logistical planning and motivation, but I needed to get lucky with the conditions. For one, there needed to be just enough snow to melt for water (as there's no water on the ridge) but not so much that it slows travel. I needed to be able to hike efficiently or it wasn't supposed to work. This is why the best time for the traverse is probably at the very end of the spring when there are just a few remaining snowdrifts as a water source but otherwise summer conditions.

Over the last few months, I'd been meticulously planning the trip. All of the logistics, mapping the route in great detail, finding all available trip reports and mining them for any usable data, downloading and analyzing historical weather data, checking webcams and checking about five different weather reports daily in the weeks leading up to the trip.

This fall set up well for weather. It was a peculiarly warm and dry fall. At first, I was excited, but then almost a little worried that not a single storm would blanket the range. But just before my window over Thanksgiving break, a small storm dropped the exact right amount of snow! Not only that, but the weather reports improved for my proposed dates. Now, a window of decent weather preceded a well-defined storm that would mark the true start of winter. This was it...the only window since spring that the White Mountain Traverse would be ready.

Backcountry bliss

After class on Friday, I drove out to Reno. The next morning, I drove to Queen Mine road on the north side of the range just north of Boundary Peak (13,147 ft), the highest point in Nevada. There, I met Paul Fretheim, owner of East Side Sierra Shuttle, who helped my car shuttle between the my car which we left at 9,200 ft and my trailhead at the base of White Mountain Peak (14,252 ft), the third highest peak in California.

I got started in early afternoon on Saturday the 23rd, and after a few hours of easy warm hiking, I reached Black Eagle Camp. These beautiful, free and well-maintained cabins are located at the old Champion Sparkplug mine, a mine operational in the 1920s-1940s for andalusite, used to make the heat-resistant ceramics in sparkplugs. It's a really splendid place, with all kinds of cool stuff from the mining days, a museum and of course the cabins.

The next morning, I got a pre-dawn start and caught the morning alpenglow on the entire High Sierra. It was a sight to behold. While most of the east ridge, one of the longest routes in the nation at 9,500 ft of vertical, is poor climbing, the setting makes it a truly special place. Part way up, I had an incredibly close, long and intimate encounter with a baby bighorn sheep and then her mother. It was a spiritual moment as we all acknowledged each other. Not only that but their tracks showed me the way up the ridge. And later in the trip, it was perhaps the bighorn tracks that helped me stay alive.

After about nine hours of climbing, I found myself alone on the summit.

As it was late afternoon, I made an effort to press on and get as much of the traverse done as possible. At the very least, I wanted to cross the first technical section in the daylight so I could find a nice place to camp. The weather was blustery, but what else would you expect on such a high summit?

I ended up not quite making it across the tricky section by nightfall, requiring that I downclimb the crux moves by headlamp. The photos below, courtesy of Summitpost.org user Daria show this section. So add in that this was at night and partially covered in snow. While well within my abilities during good conditions, it was this section of delicate rock climbing that prevented my retreat during the wind event.

The storm

Things started to pick up just as I was looking for a tent site. I finally settled on chopping a nice little platform adjacent to a col because it was somewhat protected behind some rocks. As it was a bit windy, I focused quite hard on doing everything right in my tent setup so as not to lose my tent or a pole. After guying out the tent quite well, I settled inside, melted enough snow for a liter and a half of water, had a nice dinner and settled in for the evening. A few hours into the night, things began to worsen. The tent was now hitting me in the face. What a nuisance I thought! But by the time my alarm went off for the morning, half the tent was compressed by a newly-formed snow drift. I knew I needed to keep moving to get off the ridge before the snowstorm, so even though conventional wisdom would be to hang tight in the tent, I knew I at least needed to make some progress. I packed up and quickly got moving.

Initially, I thought, wow, this is really bad weather. What I didn't realize, is that unbeknownst to me, the storm was rapidly intensifying, leading the National Weather Service to issue a wind advisory, specifically citing my region as the worst of it:

What ensued was a truly legendary storm, ultimately becoming a "bomb cyclone" (one that rapidly intensifies). The storm set all time records for low pressure of a US West Coast storm, and I had direct line-of-sight across the Pacific to Asia.

Some facts about the wind event relayed to me afterwards by the Mono County Sheriff and Search and Rescue Coordinator:

Near Mono Lake, power poles were downed. Not the lines, the wooden poles snapped. I was approximately 7,000 ft higher in elevation on a ridge.

At Mammoth Lakes Airport, a gust of 94 mph was recorded. Rocks were picked up by the wind, destroying all of the cars parked there.

The strongest wind gust recorded was at Crowley Lake, 7,000 ft below and 25 miles due west of me:

Highway 6, 10,000 ft below me was closed due to wind.

Back up on the mountain, the winds dramatically intensified when I was required to traverse saddles and flats. In addition, I believe the storm intensified. I started to get spun around when the wind caught my pack. I would lean 45 degrees into the wind, plant both trekking poles and do as hard of a lateral lunge as I could, then get blown airborne and tossed onto the tundra. At one point, I hid behind a small rock and attempted to glance at my map but was unable. It was a ground blizzard, where airborne snow and ice not only pelted exposed skin but also reduced visibility. About two hours after leaving my tent, I was in the scenario outlined at the beginning. So, what did I do? I bailed down the ridge into California. I could barely see due to the wind, but from what I could gather, it was absolutely sickening. Something I would never choose to do in a million years.

But I was past choices. From this moment on, I was on the ride.

As it was directly into the wind, I resorted to huddling during the gusts, then running full strength as low as I could before hitting the ground. Like the football sled push drill. Rinse repeat.

After losing a bit of elevation and climbing behind , things did in fact calm down. The upper ridge was quite straightforward, and even when things became a scramble it was still a joy to be a bit more out of the wind. At 11,000 ft I tried to light my stove to melt snow but it was still too windy. I pressed on down increasingly technical rock to a bit over 9,000 ft. There, I traversed on the north side (steep, snow-covered rock) to bypass four towers. As I approached the final saddle after which it would been a straightforward walk through sagebrush to the valley floor, I stopped in my tracks. Aloud, I said, "If that's my ridge, I need SAR."

I took the photos below on my phone for the sole purpose of aiding search and rescue.

At around 3:30PM and from this viewpoint, I first called Paul, then the White Mountain Ranger District in Bishop (I think the ranger there may have thought I was the somewhat typical exhausted/offroute hiker: "Well, there's no way a helicopter going to get you in this wind.") I responded, "Oh, I'm aware of that! I just need to get a line of communication going so someone can help me with a plan." I was transferred to Inyo County Sheriff and InyoSAR coordinator Victor Lawson. While first determining that I wasn't in Inyo County, and therefore he wouldn't be able to help me (DAMMMIT!) he did stay on the line, pull up my coordinates and start to analyze slopes on CalTopo. He texted me a SARtopo file plotted with a proposed route. Unfortunately, I actually had higher resolution data on my phone, not to mention super high-definition "actual vision" showing that the descent looked like hell at best. He coordinated with Mono County Sheriff and MonoSAR coordinator John Pelichowski. He gave the thumbs up to Victor and my plan, and we coordinated some other details. It was clear that this was really bad and the clock was ticking. We agreed that I would go for it, aiming for a chute they'd identified about 200-300 feet east of me. At first light, a SAR team would start up to search.

The dark art of getting down

First, I traversed back around the tower, putting the microspikes back on for the sketchy snow. After a time, I reached the saddle between the correct spires and started down the recommended chute. It was an extremely loose, tricky, then sketchy, then scary downclimb. I stopped when the rocks I was slipping on shot over the lip of a 150 foot dry waterfall. To avoid the loose rock, I chose to rock climb the buttress to the right of the chute, which went well into the 5th-class (roped rock climbing). All of the rock, from this point on, was terrible. The worst I've encountered. The largest blocks my feet dislodged were the size of a dinner table. Handholds broke.

I climbed as high as I needed to until I could traverse until the next chute west. An extremely technical rock traverse brought me into the second chute. As with the first chute, it was a horror show. It seemed everything on the face would just get steeper, ending in cliffs. These bands were too small to pick up on the satellite imagery and topo maps, but still far too big to deal with in real life: 30-150 feet. I reascended on another buttress, aiming to explore the next chute but the rock was even more technical. The chutes to my right were near vertical and the buttress was too technical to climb, so I jumped back in the loose chute to slide my way the few hundred feet uphill back to the ridge.

There, Sheriff Pelichowski and I texted. I tried to call Michelle, but almost immediately was called by her parents with confusing questions about Michelle's whereabouts. Her car was stranded in Nevada and the police were worried and looking for her! I then was called by a Santa Clara County Sheriff asking all sorts of rigamaroll about her wellbeing. Once he was sufficiently convinced that she was ok and that I had in fact parked the car in Nevada, he was like, "How are you, by the way?" It's like, dude the only reason I picked up is because I thought this was search and rescue. "Well, I'll let you get back to it then."

I did get through to Michelle as it got pitch black. I strapped on the microspikes, made another long, sketchy snow traverse back up the ridge past two towers to the largest chute. At least this one went the furthest down. Most of it wasn't that bad. I mean, normally I'd consider it horrible. But in this case, I was just thrilled to be moving downward without having to be concerned about dying each move. I made it most of the way down, traversed skiers right across a crappy buttress and dropped into the chute that I believed set me up with the best chance for success. At last, I could hear and see the stream. But I was beyond dismayed that everything in the gorge dropped into a narrow, near-vertical slot canyon. Just 150 feet above the creek, I stood at the lip of a dry waterfall.

By this point, I'd been downclimbing, reascending, and traversing for a few hours in the pitch black. I'd been cautious to eat hardly anything because I needed to focus on hydration. Over 12.5 hours, I consumed a quarter liter of water. The sound of rushing water was torture.

But at least the drainage I was in had a tiny bit of snow in it. I chose to do as I'd done before. I worked my way downstream and systematically work every single option. It's crazy to say this, but it was significantly worse than everything before. The rock was much steeper, and the traversing was outrageously hard. Fear had left me far earlier.

I worked about eight different options, each with their own challenges. One unbelievably hard rock climb up and left was about 250 feet above the black. I ascended extremely technical, poor quality rock, perhaps in the 5.6-5.7 range. Following this final buttress, I saw an easier slope in all directions but unfortunately no descent through the final 30 or so feet to the creek. In an unbelievable moment, I saw a vehicle driving up toward me in the valley! It was Paul. We communicated and ended up telling him to go home as I knew there was no way I'd get out that day.

I communicated again with Sheriff Pelichowski and I told him that I'd head back upstream to the snow and bivy for the night. I ascended high to avoid all of the cliffs and soon reached the landmark dry waterfall. I descended, eager to reach the snow patch only to find that it was just calcite deposits on the rock! From a distance and under headlamp light, I had been tricked. What an unbelievable blow. This was perhaps the lowest moment of the ordeal.

Re-ascend a few thousand feet to actual snow? There, I'd be able to hydrate and communicate. On the other hand, I'd be moving a significant distance in the wrong direction. And by this point, I was more focused on the fact that I had less than 24 hours to get out or I'd be dead. Snow was forecasted to start late afternoon or evening both trapping me and halting rescue efforts.

I made one more hail mary attempt to descend before reascending to the snow. I chose to start with...the waterfall. In a strange sort of luck, the slippery, water-polished stone actually became stickier on the streaky deposits. It felt great. I quickly descended most of the way down the cliff before the final escarpment. Here, I traversed upstream on steeper but better rock. It was clear that this was the only option that would go, as the gorge came to its most impressively vertical at this moment.

It worked. I made it work. It was outrageous, but with the slightly stronger, stickier rock, I was able to make some more gymnastic moves that would have been suicidal on the bad stuff. But make no mistake, it was extreme. It was technical. It was so messed up.

And just like that, I was at the creek on flat-ish ground. I dropped my pack, grabbed my bottle, dunked it in the stream and chugged until brain freeze. And again.

The last day

I quickly found a terrible, but workable platform to pitch my tent. Despite having jagged, microwave-sized blocks, I hastily excavated the boulders, filled in with smaller rocks and pitched my tent. My sleeping pad immediately popped due to the sharp rocks underneath, so I slept on my pack, down jacket and heavy gloves to insulate from the cold. But I was able to eat some great food, down a liter of water and get to bed by 11. After all, SAR was coming up at first light and I wanted to be moving down before dawn to give ourselves the best chance of getting through the canyon.

POP POP BOOM POP!

I instantly threw my arms over my head and braced for impact. An enormous rockfall funneled down the chute and launched over the lip of the waterfall pitch just 50 feet away, exploding on impact and sending debris toward my tent. At this point, I was resigned to the fact that I was trapped in the slot at the base of the 1,700 ft face made up of the loosest rock ready to slide. Still unable to control the situation, I fell back asleep.

I woke up, broke camp, and started down by headlamp an hour before daybreak. The canyon was immediately bushwhacking hell. The worst I've ever experienced even compared to the most choked out Sierran drainages. But it didn't matter. I belly crawled over long thickets of briars, systematically broke willow branches, and every twenty feet, forged a way through the brush to cross the creek on iced-over boulders. But it was okay...I was moving.

The first time my heart sank was when the canyon narrowed to a single slot where the stream plunged over a 100 ft waterfall. Little did I know that half a dozen waterfalls lay below. Unable to do anything but improvise, I repeatedly free soloed up the walls, traversed over awful, loose terrain, and then soloed down to the drainages. Sometimes, it took 40 minutes of sustained rock climbing to cover just 10 feet.

I tracked my forward progress on my phone counting down the feet until the mouth of the canyon. Just 700 feet from safety, I came across a final cliff band. Once again, a couple bighorn sheep tracks led to the base of the right hand cliff, where a 6 inch wide ledge ascended up and around a corner. I delicately climbed the smooth, downward sloping ledge for about 30 feet until I reached a bench, which I traversed along a bighorn trail crossing several loose chutes. At last, I found a tricky but possible talus slope back down to the final cliff. I traversed alluvium beneath the canyon floor, holding on to a tiny bush which broke. But I pulled the final move and reached the floor. After that, a tiny bit of bushwhacking, then wading through 3 foot deep leaves led me to a broad dry wash. Here, I jubilantly messaged SAR to retreat and rendezvous at the cars. I heard the team shout "Hello!" I yelled back, but got no response so I continued down. Once again, I heard "HELLOO!" I spun around and gazed upwards to three figures waving from a small summit above. I screamed and waved back, then waited as I watched them descend. It had taken six hours to cover the final mile. But it was over.

Perspective

Giving Thanks

It's hard to describe the gratitude I have to be here this Thanksgiving. In particular, I am thankful to:

Michelle and my family

Inyo County Sheriff Victor Lawson, Inyo SAR

Mono County Sheriff John Pelichowski

Mono County Search and Rescue. Donate here.

Paul Fretheim, East Side Sierra Shuttle

Max Ferrero and Mint Condition Fitness

Bringing it home

Now that the jetlag and initial fatigue have passed, I've had time to reflect on the experience and put it in perspective. This was truly one of the great trips I've taken. It wasn't perfect and there were a bunch of things that were hard to get through. For one, I wish sanitation issues hadn't plagued our team more or less from start to finish. But on the whole, I loved the experience. Again, for me it's not so much about summits (obviously it's fun and rewarding to reach them) but about the process. I really feel like I learned a lot of mountain craft and had a high enough level of training and experience to enjoy the climbing itself.

The trek out was a great experience. Though I was dealing with vision issues (which are now nearly back to normal and likely were the result of a pair of retinal hemorrhages due to lack of oxygen), I absolutely loved moving over the glacial and riverbank terrain the last few days. We had a full adventure, with stormy weather adding the challenge of soaked clothing, sleeping bags, and other equipment.

By this point in the trip, everything felt natural. The rhythm of life in the mountains became an effortless, comfortable flow. As a team, we worked well, moving seamlessly in groups on the route and helping each other at camps. By the time we reached Skardu, I'd fully shed the stress of the highest Karakoram. As Boukreev would say, I was reborn.

Mountains are cathedrals: grand and pure, the houses of my religion. I go to them as humans go to worship...From their lofty summits I view my past, dream of my future, and with an unusual acuity I am allowed to experience the present moment. My strength renewed, my vision cleared, in the mountains I celebrate creation. On each journey I am reborn.

Anatoli Boukreev

Gasherbrum, the real story

I’ve made it all the way back to Islamabad and I fly home tonight. I’m finally ready to share the story of Gasherbrum II, but first, I have a confession to make: I don’t tell the whole truth on this blog. Sometimes sensitive things happen involving other climbers, sometimes I choose to not unnecessarily scare you, and sometimes it’s just my decision to be purposefully vague and call something “challenging.” I debated how much to whitewash my account of G2, but I’m opting to be pretty honest (again, some additional details from this climb just aren’t meant for the internet). As you’ll see, climbing often is less about aerobic ability and has more to do with keeping your head in the game and responding to the curveballs life throws your way. Enough editorializing, here’s what happened on G2, at least what my fuzzy memory can reconstruct from it.

After about 8-9 days rest following Broad Peak, I was ready to move to G2. While I was originally the only one with a permit, a number of teammates fresh off a failed attempt on K2 decided to join. We made the trek from K2 all the way to Gasherbrum base camp in a day. It was a long haul as this is normally a two-day journey.

Sanitation in our Gasherbrum base camp was horrible. Notonly were there feces everywhere, but our kitchen’s soap bottle was sealed andunopened. Not a good sign. And when a teammate went to get boiled water, thekitchen staff added cold water to hot water and started to pour it. Five of uspromptly got sick. We took one rest day and my symptoms worsened. Altitude nevermakes things better. The next morning, as we climbed up through the Gasherbrumicefall, I made numerous pit stops. By the time we reached camp one (our statedgoal was camp two), I prayed that our team would collectively decide to call ita day. Fortunately, they did, and we spent the afternoon getting some much-neededrest. I was pretty beat.

The next day, we needed to go directly to camp three. We were trying to outrun a storm so we didn’t have extra days to play with. The route from camp one to three is the most technical of the route, following the famous Banana Ridge. This consisted of some particularly narrow sections of rotten ice and snow, and traversed some steep ice pillars. Again, I repeatedly needed to stop for urgent bathroom breaks, but now in high-angle situations holding onto the fixed ropes. It was a long, challenging day…any time you’re climbing to 7000 meters with a pack it takes something out of you.

Summit day

High camps are more like stopovers. You don’t really rest orget better there, so you might as well just take a few hours to hydrate,stretch out and prep for the summit push. Before “dinner” I puked. I just triedto rehydrate and relax as much as I could. Soon, we were getting dressed and packing.And finally, at 10:30PM on July 24, nine headlamps ascended into the Karakoramnight under a bright moon. The night started reasonably well. It’s never easymoving upwards over 23,000 ft but I did a great job again with my boots so I hadtoasty warm toes and everything working well upstairs. But my GI system wasstill heavily compromised. About two hours in, on a rocky section, I needed togo to the bathroom. Soon after, I vomited. It was the first time I consideredgoing down. But I didn’t seem to lose too much strength and I kept tellingmyself that if I could get to the start of the traverse (the long, gentle snowsection between the summit rock pyramid) that I could reassess there. I didn’trealize, however, just how long and soul-crushing this loose rock sectionbefore me would take. It was just the right angle and just the right size ofgravel to make cramponing up it hell. Any smaller and the crampons would haveeaten it up no problem, but at this size, every rock was poised to roll andmake you fall down. Excruciating work.

I made it to the start of the traverse, now behind the maingroup, climbing with Pasang and Mingma slightly behind. I didn’t feel badly sothe three of us roped up and began up the long snow slope to the notch at thebase of the summit ridge. As the sun came up, warming us and our spirits, Ibegan to vomit. Every so often, if Pasang pushed the pace slightly past mylimit, I’d double over and hurl. During one of these five sessions, Mingma cameup and put his arm around me. I assumed he’d gently convince me to turn around,but instead, gave a short pep talk. This would be Mingma’s 13th8000er and I knew there was no more motivated person on the mountain.

Despite the delays, we still made good time up the slope,and soon were at the notch. We’d all been praying for a gap in the weather sowe could take one proper sit down break, but when we reached the ridge, thewind was more violent than ever. All I did was apply sunscreen. I cached my smallsummit pack to jettison all possible weight over the last few hundred meters.

As we neared the top of the couloir gaining entrance to thesummit slopes, I began to hallucinate. Blurry rocks in the distance becameanimated, colorful human figures. One, I became convinced, was a dead body. Whilethis sounds alarming, hallucination, I should note, is something I’veexperienced on a number of occasions in the mountains. Even at low altitudes inthe Sierra I’ve been able to reach these altered states simply by climbing 26hours straight. In any case, cognitively I was able to recognize that what Iwas seeing wasn’t real. And on the bright side, at least the vomiting had stopped.I knew I was absolutely on empty with food and water, but I felt stronger and Iknew we were getting close.

We passed the rest of the team on their descent from the summit. All smiles, they assured us that the summit was “less than an hour,” “an hour,” and “more than an hour.” The weather closed in. It was hard to see Pasang in the lead, and Mingma came in and out of view below me. Then Pasang waved and I knew that we were about to reach the summit ridge. As I swung one leg over onto the other side, I realized it was serious. This knife-edge ridge would require all of my attention. The rope ended about 30 feet before the true summit. I unclipped, braced my hands on the firm snow and front-pointed across the precarious final slope. At 10:30AM, after twelve hours of climbing, I could climb no higher. Pasang and I sat in silence on the summit, watching Mingma cover the final slopes. After some rest, summit photos and congratulations, we began to descend. I didn’t even take a sip of water.

I am nothing more than a single, narrow, gasping lung, floating over the mists and summits

Reinhold Messner

Somewhere on the descent, Mingma politely informed me thatTam Ting had already taken my summit bag down to camp three as a favor. Great…nofood, water, mittens, goggles, you get the idea. I put it out of my mind and keptplungestepping down. When we reached the base of the lines, the weather waseven worse. Now things looked like a maze of chutes. Our tracks were covered. Wasit really possible to get lost this high on the mountain? We opted to descend asteep narrow gully (different than the one we climbed) with three or four rappelswhich brought us back to the plateau above the traverse. Then we roped together,and with Pasang’s outstanding routefinding, navigated the entire traverse untilthe clouds parted on the slopes above camp four. Mingma was toast. I feltsecretly happy that I wasn’t the one holding the rope team up as he flopped inthe snow. I ate some snow at our breaks, trying to at least moisten my mouth.We descended the awkward rubble slopes and soon the glorious tents of campthree came into view. The rest of our team was gone, opting to charge on downto camp one, but it was clear that for the three of us, at 18 hours, our daywas over. I had a feast of a dinner: two or three crackers and a cup of tea,and promptly went to sleep.

Then it got hard

We woke up at 3AM to get down before the icefall became awarm, sloppy hell. It took me/us forever to break down camp, pack and get movingbut we were finally descending in earliest light. We were in the clouds, makinga whitish, soft light which blended with the snow to make the world a fuzzy,fluffy ping pong ball. My world was especially fuzzy. At sea level, you’drecognize this right away. But at extreme altitude, when you haven’t reallyeaten or drank in a couple days, and in a moment when you just need to focusand get down, sometimes it’s hard to tell.

I don’t really remember when I realized, but somewherebetween camp two and three, I figured out, well, that I couldn’t see.

Still hallucinating? Check. Crevasses were multicolored dancingfigures. I couldn’t tell if they were right in front of me, or, as was usuallythe case, thousands of feet below me on the glacier.

Seeing double? Check. This took forever to figure out. Howcan you tell when everything’s white? On big mountains there’s usually a mazeof fixed ropes from previous years and one good one from this year. When “armrapelling” (grabbing a bunch of ropes and sliding down), I usually clip a few crappyropes for good measure. Turns out, there weren’t a few ropes. At one anchor, Icould actually see the two ropes merge into one as I was rigging a traditionalrappel on my device and discovered the visual trick.

Blurry vision? Check. This one was by far the scariest. And,full disclosure, the other issues have cleared up but I still have a pretty bigproblem here over a week later. Blurry vision was a big deal because it reallyaffected my ability to see textures and footprints, not to mention the majorstuff you shouldn’t be messing with in the big mountains.

Normally, I’m a big fan of arm rappelling. When I’m feelingconfident, I can face in, face out, quickly pass anchors, pass other climbers.It’s fast and versatile. But I soon realized that I was better off rappellingeverything I could. My vision was fine at close range, so I could reliably rigmy device and then just use good technique to get to the bottom of the rope. Thefirst few raps were textbook, and I was happy I was efficiently getting off abig mountain.

Near the end of one of the raps above camp two, I had asurprise. I’d gotten slightly to the right of the track (again, it wasdifficult to see), planted my left leg and pushed off. My right leg, expectinganother step in soft snow, dropped into oblivion as I went into a crevasse. Mymomentum pivoted me around the rope, so I inverted. I locked the ropeimmediately and kicked my left leg into the snow, flipped right side up,squatted out of the void and continued the rappel. Quite the 6AM wakeup call!

The rest of the technical descent went smoothly. I was surprisinglynot that tired. I waited for Mingma at the base of the lines as I really neededhelp knowing where to go. It was on the flat portion of the glacier that itreally became clear to me that my vision issues were going to become achallenge. The texture of the snow looked like gray volcanic ash or red clay,but the crampon marks were often completely obscured. We soon reached camp one,where Mingma Tenzing, Pasang and Tundu were breaking down the last of camp.Once everyone was packed up, we unceremoniously departed for base camp. Iinsisted that we rope up, citing the fact that I couldn’t see! It was snowing,a good sign I thought, for the condition of the icefall. Boy was I wrong.

The start of the route from camp one to base camp is a “flat”glacier. I remembered it being mostly easy walking with some crevasses alongthe way. Well, maybe, but we were also in a snowstorm so we couldn’t find themain track. Plus it was warm, making things that were normally frozen solidinto invisible death traps. I’d say about half an hour outside of camp thingsgot pretty full on. We had two rope teams: Mingma Tenzing in the front, followedby Pasang and Tundu, and a second rope with me in the front followed by MingmaGyalje. Mingma Tenzing took the lead role like a champ. It’s hard to describejust how serious of a job he had, but we were in a convoluted maze of crevasses.He would routinely hop down on his stomach and belly crawl, probing for holeswith his trekking pole. Once he’d crossed an absolutely insane section, it wasPasang’s turn. Normally, following feels a lot more secure than leading, but inthe case of Pasang, he was carrying what can only be described as a monsterpack. He was punching through absolutely every hole so Mingma Tenzing and Tunduhad to watch him like a hawk. Even I, the fourth to pass through each section,punched through a lot of snow bridges. On one occasion when a one-foot hole becamea five-foot hole when I stepped on it, Mingma asked, “You didn’t see that?” I waslike, “I did see that but it got a lot bigger!” A few times with monstercrevasses, we had to get creative. In one case, we were forced to climb downinto it and up the other side.

At last we reached the top of the icefall, and at last, Ithought, it would get easy. Solid ice! Oh yeah, I remembered, solid ice surroundedby rotten popcorn suspended above air. Easy to know what to step on if you cansee. The icefall starts with a flatter section and some really athletic jumpsover big crevasses. Fortunately, a couple of these have a fixed line. But therewere some really serious jumps that didn’t. We stayed roped up and the firstteam took off, with Mingma Tenzing again working hard to keep us on route.Things were fine if I could keep in contact with them, but whenever they gotmore than a few meters out front of me, I froze up as I simply couldn’t seewhere to put my feet. Crampon marks on snow in a snowstorm were absolutely impossiblefor me to make out. In one memorable moment, I stood on a pedestal of ice over theblack void of a crevasse. “Where do I go?” I asked Mingma? “It’s an easy jump,”he said. Seriously, where am I jumping, I thought. Below me was a teeteringblock of ice, tilted at about a 75-degree angle. “Where do I land my feet?” Hecame up beside me and pointed down about four feet with his pole. It wasseriously scary. I have to jump across and down the crevasse, stick my cramponsin the sloping ice so I don’t go in the black and I can’t even see what I’mjumping on? I leapt, didn’t exactly stick the landing, but rotated and kickedback into the ice block across the crevasse to arrest my fall. Sick.

The icefall got easier and easier as we descended, but Istill had to stick right behind someone so I wouldn’t lose the way. At 3:15PM,I strode into base camp, shared some congratulations with my teammates and ourcookstaff, and began to repack for the journey home. Mingma had made the callthat we would begin our accelerated trek down the Baltoro early the nextmorning. There would be no rest til Skardu.

G2 summit and safety

On June 25 our entire team summited Gasherbrum II and returned safely. Foregoing any rest, we departed base camp for home today and are already about 20 miles down the glacier in Goro II, albeit in a storm so everything is soaked. We have three big days ahead of us to get back to the village of Askole. I have a lot more to write about the trip but I don’t have the battery power, time or energy to post now.

We see our first plants in weeks tomorrow!

Hari

Let's play two!

Former Chicago Cub Ernie Banks radiated positivity and a love for the game of baseball. Even when the Cubs were in last place, he exclaimed, "It's a beautiful day for a ballgame. Let's play two today." In that spirit, we're going to embrace our good health, weather and simply the privilege of being all the way up here to attempt Gasherbrum II. Tomorrow, we'll make the two-day trek in one long day of fast hiking. Then, if we're tired we'll take a rest day but otherwise get directly to camp two. From there we'll likely establish a camp three though it's possible we'll only use one camp on the mountain if we're feeling super strong. This all sets up for a summit day around July 25. Afterwards, we'll officially close down our expedition, making the long trek out, jeep ride to Skardu and flight to Islamabad in the last days of July.

Base camp life

Now that the bulk of the fatigue of Broad Peak has faded, I must continue to recover as well as do tasks that keep me physically and mentally fresh. Here's a look at base camp life and some of what might happen during a well-designed rest day.

First, a quick tour of our base camp:

What about my personal quarters? I'm proud of myself for keeping organized this season, so here's a look:

Wait, how are you even sending this?

-

I brought 80 watts of solar PV -

My battery has a variety of connections -

Sat modem. The airtime is outrageously expensive. This post will cost over $50.

But you can't just sit in the dining tent and take naps and showers. Expeditions are a continual state of unpacking, cleaning, sorting and repacking gear. Today I did most of the sorting and packing of my gear from Broad Peak to Gasherbrum II. Here's a good chance to see everything I took on the four-day summit push on Broad Peak:

Counterclockwise from the yellow pack:

Everything had to fit into a 50L Black Diamond climbing pack. I also brought an extremely light Hyperlite Mountain Gear sack for summit day.

1L Nalgene, water bottle parka, thermos, pee bottle, cup and spork

Grivel G12 crampons (best snow anti-balling system by far), Camp Corsa Nanotech axe (superlight but still with steel pick and spike).

Ultralight Petzl harness with a very light and simple rack: leashes with light lockers, knife, double sling, single sling, ascender, descender, all biners as light as reasonable.

8000m triple boots

-45 degree Mountain Equipment sleeping bag

Light Mammut helmet

Missing: ski pole

Upper body clothing system:

Base layer is the pink-ish Craft wool/synthetic hybrid. Performs extremelywell and smells pretty good all things considered.

Mid-layer: Jagged Edge PowerWool hoody. Wow. It's basically a Patagonia R1 that doesn't smell. Shoutout to Jon Miller and Erik Dalton at Jagged Edge in Telluride, CO!

Shell: Arc Teryx Alpha FL goretex jacket. I'm in the process of destroyingthis jacket by "arm-rapelling" down the ropes. I'm estimating thatI'll arm-rap over 50,000 ft of rope this season, so that means goretex jacketsand leather work gloves are likely to get donated in a few weeks. Also, it's beenpretty warm this year in the Karakoram so I've sometimes gone with the shelldirectly over the base layer. Not too much insulation but still with theprotection of a hard shell.

Insulation: Thin Patagonia Primaloft insulated layer. This thing is takingan absolute beating but still holding up! In and out of the pack at every breakbut mostly I try to climb fast enough that I skip it.

Super insulation: That's the big orange puffy. Didn't use it until summitday but boy was I glad I had that ace-in-the-hole piece. Thank god for thegigantic hand pockets.

Head: Buff (If you don't know about a Buff you need one!), Patagonia balaclava, baseball cap under the helmet for lower mountain, photochromic glacier glasses, photochromic ski goggles.

Hands. OK this is where it gets ridiculous. I'm trying to simplify Ipromise! Hestra leather Ergo Grip gloves. These will be toast by next week.Mountain Equipment Randonee Gauntlet gloves. I used to be sponsored by theseguys. I bought these full retail. Hestra something or other heli gloves. Notquite as warm as I would have hoped high on Illimani or here on Broad Peak butstill quite a good glove. I brought these on summit day. The North FaceHimalayan Mitt. Freakishly warm but I was unable to perform the required ropework on summit day because they were too bulky.

Lower body clothing system:

Light blue Simul Alpine Patagonia pants: These are great, especially nowthat I've added an elastic belt (waist size changes dramatically over a trip).They're also slim enough that they don't tend to catch crampon pointsaccidentally. Not only do you look like an idiot but getting caught up on yourpants in the wrong situation can be really bad. No baggy climbing pants!

Ex Officio underwear

Craft long underwear: I love these long underwear. But on Broad Peak Ididn't wear long underwear below 23,000 ft. Long johns are for the weak!

Mountain Hardwear fleece tights: I went straight to these on summit day. I like how they can withstand some weather, so it's ok to open the side zips on down bibs when really working hard.

Mountain Hardwear Nilas (down) bibs: I've been in love with these since2013. They were just right on summit day.

Medium wool socks (Darn Tough), thick wool socks (Icebreaker). Just take off your wet stinky wool socks and dry those bad boys on your chest for the next day.

Take a hike!

Hiking is important for your fitness, sanity and just because you have the privilege of living in one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

I recently took a trip to the Gilkey Memorial, named for American Art Gilkey who died here in 1953. It has since become a memorial site for all of those who have died on K2 and nearby peaks. It's bigger than I was prepared for and it's a profoundly sad place to visit.

Let me guess, you use the *correct* amount of oxygen?

You get these high-powered people who want to climb Mount Everest...there is a Sherpa in the back pushing, carrying extra oxygen bottles so you can cheat the altitude. You haven't climbed Everest. The purpose of climbing something like that is to affect some kind of spiritual or physical change. When you compromise the process, you're an asshole when you start out and you're an asshole when you get back.

Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia

Why do I keep incessantly repeating “without oxygen”? Because climbing with modern oxygen systems is like dunking on a 6 to 8-foot rim. Sure, it counts for something, but it’s not exactly the same as a regulation hoop. First, there is the extremely large group of people, me included, who simply don’t have what it takes athletically to get up there. Second are the players who develop the ability on the practice court over time. I saw a few freakish 8th graders reach this level. But it’s an entirely different story to dunk in an NBA game. Now you’ve given up sole control of the situation and have a whole new set of variables to navigate. This season has been amazing in that I’ve had phenomenal teammates who stole the ball and passed it to me in the open backcourt of good weather. No between-the-legs antics for me: I puked five meters below the summit, then sluggishly executed a simple one-hander. But that’s right: I just fucking dunked in an NBA game.

Oxygen is ridiculously awesome. It’s the most immediatelyessential molecule we need to survive. Climbers who use oxygen think clearer,sleep better, eat better, climb faster, have warmer fingers and toes, and, tobe blunt, die a whole lot less. To put modern oxygen use into perspective, I’vebeen the strongest and most skilled member of my team on every commercial tripI’ve been on. When the other members switched to oxygen, I became the slowestand biggest liability.

But oxygen sanitizes the experience. It brings the mountain down to your level instead of ascending with integrity. It rewards the outcome (for lack of a better word, summit) over the process.

If there is such a thing as spiritual materialism it is displayed in a desire to possess the mountains rather than to unravel and accept their mysteries.

Voytek Kurtyka, The Art of Suffering

I recently learned that I have a (totally light-hearted) reputation in the Himalaya for “running away” from big mountains. For not getting to the top. In the world of commercial mountain tourism, I suppose I’d have a more filled-out resume if I were a 2x Everest summiteer, 2x K2 summiteer, and Lhotse summiteer. But what are we counting? Why? Would the other clients have credentials at all if they had to breathe that thin Mount Everest air for what it truly is? A high-end operator recently confessed to me that they've essentially eliminated the altitude factor on Everest! Other variables like health and weather may shut them down but that raw struggle at altitude was effectively offset by high oxygen flow rates. I worry that we’ve lost our collective creativity, self-expression and self-determination when we select our goals off company websites and view life as artifice.

For myself, I consider the use of supplemental oxygen by modern climbers to be cheating--not like blood doping or steroid use, but an unwillingness to climb the mountain on its own terms. If a climber isn't able to reach the top without supplemental oxygen, it would be better to climb a smaller mountain.

Steve Swenson

There’s an elegant solution to a lack of high peaks at your level: climb lower mountains! They’re incredibly beautiful, in many cases you’ll get a greater sense of adventure, they’re cheaper, the trip is shorter, and don’t think for a second there’s not enough challenge for you there. I’ll continue to pursue lower mountains out of their sheer majesty and solitude over the eerie, dreamlike trance of 8000-meter peaks.

There are a dozen reasons for climbing, some bad, and I've used most of them myself. The worst are fame and money. Commonly people cite exploration or discovery but that's rarely relevant in today's world. The only good reason to climb is to improve yourself.

Yvon Chouinard

But if that isn’t your taste, I have no hard feelings. I don’t make the rules. Mountains are a canvas for our personal expression. Short of environmentally trashing these spectacular places or exploiting local people, they are open to our interpretations and always should be. Mountains are my religion and I hope that you worship beneath whichever cathedral inspires you.

Humility and respect,

Hari Mix

Realization

Weather continues to improve: summit bid starts tomorrow!

Alpinism is not just the act of ascending a mountain, but also inwardly of ascending above yourself Voytek Kurtyka

Things keep developing smoothly and quickly here in the Karakoram. Tomorrow around 5AM (5PM Tuesday Pacific Time), our team of five will depart for the summit of Broad Peak. Along with me, the team consists of: Tobi, a German climber and skier; Pemba, a climbing Sherpa from Khumjung, Nepal climbing with Tobi; Phurba Gyaljen, a climbing Sherpa from Thame, Nepal climbing with me; and Sirbaz, a high altitude climber from Hunza, Pakistan climbing with me). We plan to make a 3-day attempt with a possible 4th day for descent. On Wednesday, we'll climb to camp 2, Thursday camp 3, and Friday summit and descend as far as possible.

In an hmix.org first, I'll be attempting to share the experience live (much more boring than it sounds) using the Where's Hari? link at the right of the menu bar on the main page. I'll do daily check-ins after our climbs and then on the summit day I'll attempt a live track.

Live track details: We plan on starting for the summit at 8AM Pacific time Thursday. Yes, that means we're waking up at 7PM and climbing all night.

Live track expectations: I've never tried a live track before so it may not work. The device is programmed to track at long intervals of 30 minutes to conserve battery. But in the extreme cold, my device may shut off so if the track ends abruptly please assume it's a technical problem. It's gonna look pathetically slow both because it will be pathetically slow and also because the mountain is steep. You may want to check our altitude as opposed to relying on the map to show position. The summit is 8047m (26,401ft).

Summit day on Broad Peak is considered extremely long and difficult even by 8000m peak standards. I'm expecting a 20+ hour all-out effort with more gas in the tank in case we get slowed down. So, in summary, don't worry if it looks like we're barely moving or if there's a malfunction. No news is good news.

Have a great week!

Hari

Full Rotation

In order to climb any truly huge (let’s say over 23,000 ft)mountain, it’s essential to perform “rotations” where climbers exposethemselves to the harsh higher altitudes and then retreat to recover. Capitalizingon good weather, good health and a “get after it” attitude, I have completed myacclimatization (and the accompanying task of getting all of the right gearcached in the right places) in as fast a time as I have ever done. Now I’m abit tired, deservedly so, but resting, eating as much as possible and waitingfor the right opportunity to summit Broad Peak, the world’s 12thhighest mountain, without supplemental oxygen.

So here’s what we did: Arrive in base camp and take two restdays. Then touch camp 1, which is about 18,000 ft and return to base camp.After two rest days, we returned to the mountain with heavier packs and climbeddirectly to camp 2, about 20,000ft. The following day we ascended to camp 3(high camp) at 23,000 ft. I climbed a bit higher without a pack as this aids inacclimatization. The day before yesterday, we descended all the way to basecamp, caching supplies in camp 3, camp 2 and near the base of the mountain.

The route starts with an awful shortcut from K2 base camp to the bottom of Broad Peak. Because of the amount of recent snowfall, this section is a convoluted mess of glacier and moraine with many hidden crevasses. It’s rapidly melting out (which is nice if you prefer seeing your crevasses), but bad because every time, the glacier looks different making routefinding more challenging. It’s a maze of ice towers, rocks, bottomless snow, icy ponds, and weak snow bridges waiting to break and plunge you into icy creeks. The base of the route is a narrow snow gully next to a large rock cliff from which there is rockfall…best to keep moving. Passing over a few giant crevasses in the initial gully, the route weaves to the right up a broad rock and snow face. Camp 1 is located on a ridge, one that will be followed to gain access to the upper mountain. The route continues to be mixed snow and rock to spectacular camp 2, where Concordia and the central Karakoram make up the view, not to mention K2. For me, climbing from camp 2 to camp 3 was where things started to get difficult. For the most part, the climbing was technically easier snow climbing, but the effort to gain each meter really set in. There were a couple icy sections which required the extremely demanding technique of “front pointing” (using your crampons to stand on your toes only), which even at sea level can be the calf raises from hell. Though our pace slowed, our group was good natured and enjoyed a fine but demanding day of climbing together.

Climbing to 23,000 ft (higher than any mountain outside of Asia) is quite an accomplishment. Camping there is another kind of hell. I felt good overall but my stomach hasn’t been consistent up super high. For dinner and breakfast in total, I had a tiny bit of Ramen noodles, mostly broth, a bite of rice, an energy gel and a few sips of Coke. I’ve been eating great in base camp and during the climbs, so I’m going to try to keep it up and just go by feel up super high. This visit, I barely ate in camp 3 but at least I didn’t puke and lose my hydration, electrolytes and energy as in my aborted K2 summit attempt in 2017.

The fast acclimatization schedule is a pretty interesting concept. The lure of the strategy is obvious…it’s extremely challenging to be at altitude. It’s hard to describe just how weak, sick, apathetic, and even devoid of your personality you can get. Especially when acclimatizing to a new higher altitude, the process is typically painful and difficult. Every moment at altitude takes something out of you. Keep in mind that no permanent human settlements exist as high as our base camp and base camp is pretty much heaven compared to high camp on these mountains.

Who wouldn’t want to accelerate the acclimatization process? Well, just like endurance or strength training, the key comes in balancing stimulus vs. recovery. If you are strong enough, you can climb high to expose yourself to altitude, then retreat quickly to avoid its destructive effects. But buyer beware: if this were truly an easy shortcut, then everyone would do it. Funny how you keep seeing these professional athletes and Olympians training 1000+ hours per year instead of opting for 20-minute high intensity interval workouts or the latest supplement to reach their goals ;-) In my case, this rotation strategy worked very well this time but it required excellent fitness and a lot of experience at altitude to know this was beneficial exposure and not something dangerous. I still have an extremely hard task ahead. I’ll need good health, weather, coordination with other teams, and a ridiculously big effort to reach the summit.

On to more pretty pictures!

-

I've long fantasized about paragliding off the world's highest peaks. What more stylish way to get back down? Here, a German climber and pilot whooped and hollered all the way down to base camp in about 10 minutes

-

A supraglacial lake below K2

Onto the ice

This post chronicles the transition from the green human worldto the elemental landscape of rock and ice where we are only visitors. Unliketreks in Nepal and the like, this trip requires three days of glacier traveljust to reach the base of the Karakoram giants.

June 26: Urdukas to Goro II

This is one of the shorter days of the trek. After an hour orso with the group, I was feeling good and used the opportunity to “stretch mylegs.” I often find a day or two on the approach to open up my stride and walkat my own pace. I make sure to keep my effort under my aerobic threshold (thepoint where breathing does not “break away” into a labored rhythm). For me,this is a heart rate of around 130 bpm at sea level. I also enjoy the alonetime to clear my mind away from the organized chaos of the expedition. I spenta few hours walking with a ~14 year old porter. Though he couldn’t speak a wordof English, we connected a bit and shared some of my lunch. Goro II is a stark contrastfrom Urdukas and the camps below as it’s on the ice and completely exposed towind. There’s also a definitely a human waste issue. A member of another teamfell seriously ill here.

June 27: Goro II to just below Iranian Camp

This turned out to be an epic day. The story all season hasbeen the incredible amount of snow. An expedition before us was stopped heredue to waist deep snow…far too much for the donkeys and porters to handle. Theporters have minimal footwear, often just socks and sandals. To overcome thisobstacle, we were attempting a new variation on the route, which hugs the leftside of the glacier. We quickly realized that this was a challenging choice asthe trail went up and down constantly—something that wore us out and that we knewwould be an ordeal for the porters and animals. Nonetheless, we marched on andreached our destination, near Iranian camp, after a long effort. After severalhours of waiting in the cold into the early evening, we began to get concerned.After all, we were sitting on a glacier at about 16,000 ft with no resources,no means of communication and no idea how everyone else below us was faring.After some time, the sirdar (head staff member) ran up and told us we had toretreat. After changing back into our hiking clothes, we hiked down the glacierwhere we soon found our team.

June 28: Final stretch to K2 base camp

This is always an exciting day. At last we get to put our packs down, build camp and settle in to relaxed base camp life. I hiked with Ibrahim, our kitchen runner/server, and found the Sherpas hard at work when we arrived in camp. It’s really quite an effort to flatten out a glacier and stack rock platforms for the kitchen, dining tents, and camping tents. While I’m not nearly as strong, I pitched in for an hour or two, allowing me to not only show good faith, but also to scope out a good tent site (in case you ever are in the market, you’re looking for something a bit of a distance away from the kitchen and main trail through camp). I helped build a perfect spot in ‘the suburbs’ with spectacular mountain views.

Made it to the bottom!

After two weeks of travel, logistics and trekking, I’vearrived at K2 base camp in one piece. This trip, I’m going to try (given mylimited electricity, internet and effort) to give a more detailed lens intowhat an expedition is really like. Frankly, it’s what I’ve wanted to read thiswhole time so why not start sharing now?

I arrived in Islamabad’s beautiful new airport on June 16after about 30 hours of travel. The next morning, our team flew to Skardu. Unfortunately,during check-in, I puked in a trash can. GI issues seem to be one of the nearlyinevitable aspects of this type of international travel. I haven’t recoveredfrom this bug but I feel like I’m on the right track now.

We had to spend an inordinate amount of time in Skardu “waitingfor permits,” which I think is a Pakistani catch-all excuse. What really happened,I believe, is that our operator, who is running three expeditions, wanted themall to go together so he could save money. As soon as the third team arrived,magically our permits were issued! Anyhow, we’re being well taken care of so I’dbetter not complain too much!

I’ll break the trek into two portions, covering the legs tothe glacier here and the glaciated portions next.

June 21: Skardu to Askole

One of the classic crazy jeep rides in the world! I was actually astonished to see how good the road has become. It’s been steadily improving over the years. This time there were only a few sections where I felt like we were going to fall into the raging Braldu river. I don’t have photos this year but do reference my 2017 K2 coverage to see just how wild this ride can get.

June 22: Askole to Jhula

Arriving in Askole you get a sense of just how big of anoperation a Karakoram expedition is. To support our expedition, we hired 219local porters, each earning about $12/day. A standard load is 25 kg (60 lbs).These guys are literally hungry…I always tried to give about 1/3 of my lunchaway. There are also quite a lot of donkeys, though as you’ll see in the photosthis is a very challenging route for them as well. A donkey carrying one of my bagsfell into a water-filled crevasse. Fortunately, the donkey was rescued thoughmy bag was absolutely soaked.

On to the walking! Setting off from Askole is alwaysexciting. It’s the start of a long journey and the last glimpse of a road forover a month. The first two days of this trek are quite challenging. They’re bothlong and relatively flat, but with awkward rounded cobbles and sand. Not tomention the weather, which can range from 100-degree heat to snow. It’s hard toprepare for and the conditions are always changing. Fortunately for us, thesedays were mostly cloudy which made the temperatures less brutal.

One of the most challenging aspects of the entire trek is that all of the equipment must be packed and then transported all while you have already started walking, meaning that all of the team’s resources are quite far behind. This is no truer than on the first day, where porters pick up their loads, go home, eat breakfast and say goodbye to their families all before starting to walk (at a slow pace as they’re carrying a heavy load). This year was the most extreme example of this, where we arrived in Jhula six or seven hours before most of our things. For this reason, I always carry much more clothing than I’d ever normally need including things like down booties, synthetic insulated pants, lots of jackets, fresh base layers and always a pair of dry socks.

June 23: Jhula to Paiyu

Rinse and repeat. This is a big and deceptively hard dayalong the Braldu River. Conditions constantly change and the trail just keepson going.

June 24: Paiyu rest day

Not much to report here! I did very little aside from eat asmuch as I could. In 2017 we skipped this rest day and I greatly appreciated theaccelerated schedule, but this is a big deal for the porters if no one else.

June 25: Paiyu to Urdukas

Possibly the hardest day on the trek. There’s a lot of elevation gain, a lot of loose rock, a fair amount of scrambling on boulders, glacial river crossings everything. But you’re rewarded with some of the finest mountain scenery in the world. This is where you leave the metamorphic rocks behind and enter the world of granite and ice. First the Cathedral Peaks, then Uli Biaho and the incomparable Trango Towers come into view. I believe Urdukas is the best campsite in the world. It’s also the last grass we’ll see for a month.

Bonus tidbit: I'll discuss my technology setup in greater detail later, but this took hours to do. I had to charge devices and plan for this yesterday, and now I sit in my tent in a snowstorm. My fingers are too cold for the trackpad to recognize. Good times!

Skardu

I bounce on the back of a motorcycle through bustling Skardu. Fida expertly navigates through the maze of livestock, motorcycles, cars, buses and tractors hauling huge loads of gravel. My senses jolt to life: the dust, diesel smells, horns and sounds of daily life consume me. These are the experiences that I crave. Those that are so different than my everyday on-demand unlimited American lifestyle. Things are slower. They’re simpler. And certainly a bit rougher around the edges.

I’m back in the Karakoram for another season to practice my mountain craft. I’ll continue working on a lifelong project that began in earnest in 2010 with my first high altitude climbing expedition. Since then, I have spent a total of a year and a half on the world’s biggest mountains. And on this, my 14th expedition, I am once again attempting to climb an 8000m peak (one of the world’s 14 highest mountains) without using supplemental oxygen.

Tomorrow, our team departs Skardu for Askole, the last village before beginning the weeklong trek to K2. While I’ll be living in K2 basecamp for a month, I’m actually attempting nearby Broad Peak and Gasherbrum II, the world’s 12th and 13th highest mountains.

People here are warm and generous. Fida offered to buy me a piece of climbing equipment. A pharmacist gave me an item as my 1000 rupee note (approximately $8) was far too large of a denomination for him to break. A boy approached me with friendly conversation to practice his English. And when my necklace broke, a man ran after me to return it. Let’s hope this spirit of cooperation carries into the mountains. It will require a team effort to solve of these enormous icy puzzles.

Integral: The Illimani Traverse

Then it came time for the last climb of the trip. And this one was by all measures big. A complete traverse of the Illimani massif, consisting of about 9 miles of technical terrain, most of it over 20,000 ft. At 21,122 ft, Illimani is the highest peak in the Cordillera Real and the second highest in Bolivia. This time, we were joined by Bolivian aspirant guide Marcelo, who added a great energy to our rope team. We stripped down light, opting to go for speed rather than comfort on our attempt. We planned two bivouacs on the route, with both locations just below the glacier where we could access running water to save gas. On our main day, we climbed for 20.5 hours straight, mostly in truly "heads-up" terrain, where absolute focus on the task at hand was critical. For hours on end, a slight mistake or lapse in judgement by any one of us could have led to disaster. We often dealt with challenging unconsolidated snow conditions, which made not only for difficult forward progress, but also upped the risk. It was also violently cold and windy...none of us felt fingers or toes for much of the outing. Nonetheless, and light on sleep and nutrition, Marcelo, Alex and I made it back down to a gorgeous meadow on the morning of our third day and had enough energy to rally for a nice, celebratory end-of-the-trip dinner in La Paz. In the photo essay below, pretty much every time you see a ridge, we were on it.

The West Face of Huayna Potosi