Summit to Sea Microadventure

I've long been inspired by Alastair Humphreys and his brand of "microadventures." There's just so much freedom and enjoyment to be had close to home. What better time to try this new style than mid-quarantine?

My mission was elegant: Make it to the Pacific coast and back. My rules were simple: Leave from home. Take as little as possible. Maximize trail and off-trail terrain while minimizing road. Travel as fast as possible by foot.

The result was a fantastic little adventure. Definitely more "character-building" than fun at some points. But overall it was beautiful, liberating and an immersive escape from our predicament. Hope you're all doing well!

Suburban assault microadventure from Hari Mix on Vimeo.

Top 10 social distancing moments of the decade

Boredom presents a very real, if insidious, peril. To quote Blaine Harden from the Washington Post: "Boredom kills, and those it does not kill, it cripples, and those it does not cripple, it bleeds like a leech, leaving its victims pale, insipid, and brooding...Rats kept in comfortable isolation quickly become jumpy, irritable, and aggressive. Their bodies twitch, their tails grow scaly."

Jon Krakauer, "On Being Tentbound," Eiger Dreams

Growing up, I would read and re-read mountain literature. One piece that has always stuck with me is Jon Krakauer's "On Being Tentbound," which describes the all too common ordeal of being stuck in a tent in bad weather while on expedition. I've been tentbound on numerous occasions and always smirked as I know this is what Krakauer warned me I'd signed up for.

How's it going for me these days? Not particularly well. But I'm enjoying leaning into being tentbound and sort of embracing the suffering. That's one part of mountain trips I genuinely enjoy: acknowledging when things are getting tough.

So, in this moment of reflection, I figure I'd share the ten most socially-distanced moments of the last decade. Starting with...

10. Camping alone on the summit of Shasta, winter.

Just before the pandemic really got going and shelter in place orders went into effect, I traveled to Mount Shasta and bivouacked on the summit. The stars were unbelievable.

9. Little Switzerland

In 2014, Brad Lipovsky and I traveled to the Pika Glacier in Denali National Park. A ski plane dropped us off and picked us up 9 days later. In the Alaskan summer, it was light 24 hours a day, so we became nocturnal and climbed beautiful granite lines by night. The feeling of remoteness was palpable...except when the planes landed each day for tourist photo ops.

8. The Absarokas

The Absarokas are one of Wyoming's wild ranges, seeing much less attention than the nearby Tetons or Wind Rivers. I helped teach a field course there several Septembers and we had wild experiences each time. Perhaps the craziest was when grizzlies came into camp and pawed under the vestibules of several tents!

7. Jarbidge

Where's the furthest from a paved road in the lower 48? Jarbidge, NV. On the three-hour drive north from Elko, we ran into an absolutely apocalyptic Mormon cricket plague. The roads were slick from their corpses, and the others cannibalized in the tire tracks. Camping in an environment where the entire ground was moving (and crunching!) underfoot was an absolute nightmare. EWWWWWW!

6. Gasherbrum II

On the summit of the world's 13th highest mountain, I felt alone. OK, technically, I was with people. Pasang and Mingma Gyalje. But that was it. And it was a storm. Rappelling down on the border of China and Pakistan I knew we had to get everything right if we wanted to see people again.

5. The Pamir

Tajikistan is the world's 3rd or 4th least visited country at just 4000 visitors per year. And hardly any of them come over the Karamyk pass, formally closed to foreigners. Fortunately, my handlers had pre-bribed the military with cigarettes. And I can assure you none of them are alpinists...the customs officers laughed at our tourist visas.

4. The Whites

The wildest, most remote and longest stretch of tundra in the lower 48 belongs to the White Mountains of California and Nevada. I learned just how far they were from civilization when I was caught in a ferocious windstorm during November, 2014.

3. The Inylchek

In 2015, I walked alone up one of the world's greatest glaciers, the Southern Inylchek in Kyrgystan into the heart of the Tian Shan. Even though I broke my toe on day one, I had a wonderful and life-changing trip. This is as good and as wild as big mountains get. And the rivers draining them...forget about it.

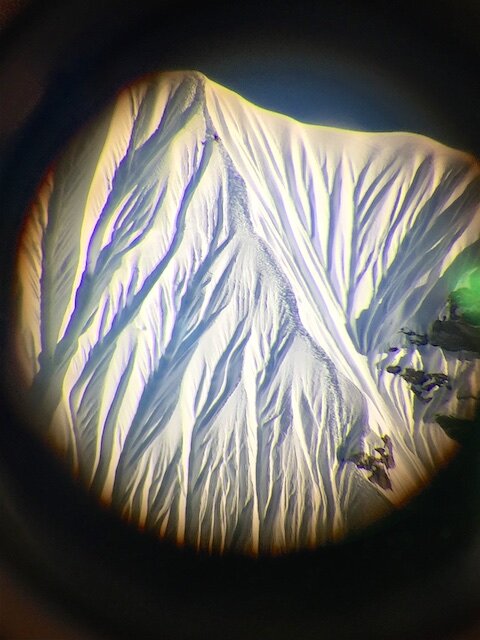

2. Rolwaling

How profoundly wild is Rolwaling? Just look at the header of this site...I'm ascending the final few meters to the foresummit of unclimbed Langdung. Within sight of Everest but receiving only a fraction of the attention, Rolwaling is a stunningly beautiful valley with wonderful people. But in order to get there, you'll have to earn it, as the road ends down low in the rainforest.

1. The Gobi

I'm heavily biased towards the mountains, so this is high praise. I've never felt more vastness, more small, than when I crossed Mongolia's Gobi desert in 2012. Not only is Mongolia the world's least populated country to begin with, but the inhospitable landscape in the southern part of the country is incomparably remote. We drove for four days without seeing anyone, navigating only by GPS and sometimes covering just 5km in an hour. It felt like being out at sea. Did I mention we found multiple dinosaurs?

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going.

No feeling is final.

Rainer Maria Rilke

The Pivot, Part Two: Physiology of a Comeback

"Every alpinist who climbs 8000-meter peaks searches for ways to prepare the body so that it will adjust to the variables. The environment at extreme altitude is as alien as outer space; the dynamics play out in ways we cannot fully understand. A mountaineer can only hope that a commitment to constant training will prop up his or her ambitions to explore the Earth's highest reaches." -Anatoli Boukreev

I have a confession to make: most of the climbing I’ve done in the past has been off the couch. It’s not that I don’t believe in training…far from it. But I think due to a combination of being lazy and rarely encountering my fitness to be a limiting factor, I simply chose to go climbing. But after last year, I knew I’d lost a lot of my overall athleticism, not to mention the mental fitness required to tackle big objectives in the alpine. Here, I’ll outline my approach to getting ready for the mountains, heavily influenced by my background in distance running and by works such as Mark Twight’s Extreme Alpinism and Steve House and Scott Johnston’s Training for the New Alpinism. These are outstanding resources.

I have a confession to make: most of the climbing I’ve done in the past has been off the couch. It’s not that I don’t believe in training…far from it. But I think due to a combination of being lazy and rarely encountering my fitness to be a limiting factor, I simply chose to go climbing. But after last year, I knew I’d lost a lot of my overall athleticism, not to mention the mental fitness required to tackle big objectives in the alpine. Here, I’ll outline my approach to getting ready for the mountains, heavily influenced by my background in distance running and by works such as Mark Twight’s Extreme Alpinism and Steve House and Scott Johnston’s Training for the New Alpinism. These are outstanding resources.

First, I follow a progressive, periodized approach to training. This means that my preparation and climbing cycle consists of distinct phases, starting with a transition into training. When running was my full time gig, our coaches often referred to this period euphemistically as “active rest.” In college, I usually pounced on the week or two of freedom to go climbing. So starting this past late December, I started to very slowly build back. I could feel connective tissue straining, but I adhered to the main rule of this period: don’t get injured. Most important, certainly for alpine climbing, is the base phase. This is where the vast majority of work gets done, and for something as aerobically demanding as my objectives this summer (I’m targeting summit days to be 18-24 hours of brutal aerobic effort, but I’d like to be able to climb for 40+ hours without food, water or rest in a survival situation). In short, I need to be resilient. The base period is where this capacity to endure comes from, and it's all about relatively easy aerobic exercise. Since ankylosing spondylitis ended my running career in 2009, I opted to use biking and hiking as my primary modes of aerobic work. Of all the aspects of training, this is the one you can’t cut short. As Coach Weisend would say in high school, “You can’t pay someone to run your miles for you.”

Most important, certainly for alpine climbing, is the base phase. This is where the vast majority of work gets done, and for something as aerobically demanding as my objectives this summer (I’m targeting summit days to be 18-24 hours of brutal aerobic effort, but I’d like to be able to climb for 40+ hours without food, water or rest in a survival situation). In short, I need to be resilient. The base period is where this capacity to endure comes from, and it's all about relatively easy aerobic exercise. Since ankylosing spondylitis ended my running career in 2009, I opted to use biking and hiking as my primary modes of aerobic work. Of all the aspects of training, this is the one you can’t cut short. As Coach Weisend would say in high school, “You can’t pay someone to run your miles for you.” Additional components of my base phase were mostly designed for me to gain some functional strength. I focused on core strength as well as coordinated body weight exercises like pull ups, push ups, dips, lunges, squats as well as some truly goofy looking balancey sequences. Once I’d gained a solid foundation there, I started focused on developing max strength in a few key areas that I find useful on really big mountains like quads, triceps and a few other areas. I added in maximum-intensity, 8-second hill sprints to develop maximum power in my quads. I quickly felt the gains on climbs on the bike and when carrying a pack.

Additional components of my base phase were mostly designed for me to gain some functional strength. I focused on core strength as well as coordinated body weight exercises like pull ups, push ups, dips, lunges, squats as well as some truly goofy looking balancey sequences. Once I’d gained a solid foundation there, I started focused on developing max strength in a few key areas that I find useful on really big mountains like quads, triceps and a few other areas. I added in maximum-intensity, 8-second hill sprints to develop maximum power in my quads. I quickly felt the gains on climbs on the bike and when carrying a pack. Next up, things start to get fun…converting these general gains into more specific fitness required for the mountains. One of these was improving the efficiency of my fat burning metabolism. In the high mountains, it simply isn’t possible to eat enough to fuel your climbing. So training in a way that makes you highly dependent on carbohydrates really can backfire, leading to the classic “bonk.” To address this, I started taking morning bike rides of 3-5 hours with 3-5000 ft of climbing without breakfast or any food along the way. The other improvements I wanted to make were in muscular endurance and improved efficiency in high altitude climbing movements (kicking steps in steep snow and ice, plunging through deep snow with a heavy pack, etc). I did this in the best way possible, a quick alpine climbing trip in Peru!

Next up, things start to get fun…converting these general gains into more specific fitness required for the mountains. One of these was improving the efficiency of my fat burning metabolism. In the high mountains, it simply isn’t possible to eat enough to fuel your climbing. So training in a way that makes you highly dependent on carbohydrates really can backfire, leading to the classic “bonk.” To address this, I started taking morning bike rides of 3-5 hours with 3-5000 ft of climbing without breakfast or any food along the way. The other improvements I wanted to make were in muscular endurance and improved efficiency in high altitude climbing movements (kicking steps in steep snow and ice, plunging through deep snow with a heavy pack, etc). I did this in the best way possible, a quick alpine climbing trip in Peru!

The Pivot, Part One: Crash and Burn

“Allahu akbar! Ash-hadu an-la ilaha illa llah”The morning call to prayer jostles me awake at the unholy hour of 3AM. As I roll over, the light body aches and night sweats of the fever I’m running add to the unpleasantness of the moment. It’s Ramadan, and the chanting over the loudspeaker serves a practical purpose for the Skardu locals: it’s their last chance to eat until sundown. At our northerly latitudes, people here will be fasting for 18 hours each day until we arrive in base camp next week. In any objective sense this is a strange time and place for me, but for some reason, I feel at home. More than ever, now I must go to the mountains as a process, a practice, a return to fundamentals.Just a few months ago, I wasn’t even sure I’d be functional enough to make it here. To say last year crushed me would be an understatement. The short story is that my mom died. The long story is a circuitous inward journey to depths of myself that I didn’t even know existed. I moved home last March following my mom’s terminal breast cancer diagnosis. Showing the hallmark signs of Pierce family stubbornness, she furiously resisted my return home saying I should focus on work, but I could tell things were descending into chaos and everyone else urged me to apply for Santa Clara’s generous family medical leave. The first month and a half or so were filled with endless appointments, phone calls and meetings to get her things in order and streamline my grandfather’s affairs. We took time to fit in some of mom’s favorite activities: putting together puzzles, going to meditation groups and bossing me around in the garden ;-) During one last trip to the beach with friends in April, however, her condition worsened to where she went on oxygen 24/7 and even went so far as to take a quarter of an anti-nausea tablet. Despite constant and excruciating trouble breathing, she managed to resist medications even in her last hours. For her, my hunch is, the integrity of the process was more important to her than even the worst life had to offer.

Over the next few months, her condition progressed and layers of her independence, personality and dignity faded. New and unforeseen problems abounded. For a while, patchwork solutions such as my teaching her the “rest step,” a high altitude technique to save energy, served as a temporary way for her to ascend the stairs to her bedroom. Negotiations over her move downstairs into a hospital bed produced some of the greatest anger and irritability one could experience. Then, one weekend in the beginning of August, fluid enveloped her heart and lungs drove her into constant and unmitigated torture.

Over the next few months, her condition progressed and layers of her independence, personality and dignity faded. New and unforeseen problems abounded. For a while, patchwork solutions such as my teaching her the “rest step,” a high altitude technique to save energy, served as a temporary way for her to ascend the stairs to her bedroom. Negotiations over her move downstairs into a hospital bed produced some of the greatest anger and irritability one could experience. Then, one weekend in the beginning of August, fluid enveloped her heart and lungs drove her into constant and unmitigated torture. The disease walked a tightrope between life and death, creating the sensation of drowning, vivid violent and paranoid hallucinations and profound nausea. The eerie parallels between her cancer and the symptoms of mountain sickness and the struggles to survive I’ve faced in the high mountains were not lost on me. Health crises manifested at all hours of the day and night, and multiple times we saw all the resources hospice had to offer. Finally, after six weeks of the worst suffering one can experience, she took her last breath, the trials of taking on cancer on her own terms over at last.

The disease walked a tightrope between life and death, creating the sensation of drowning, vivid violent and paranoid hallucinations and profound nausea. The eerie parallels between her cancer and the symptoms of mountain sickness and the struggles to survive I’ve faced in the high mountains were not lost on me. Health crises manifested at all hours of the day and night, and multiple times we saw all the resources hospice had to offer. Finally, after six weeks of the worst suffering one can experience, she took her last breath, the trials of taking on cancer on her own terms over at last. For a couple months I held my shit together. During September and October, I routinely logged 16 hour days settling her affairs, working on the house and getting ready for a move back west to return to Santa Clara full time for the winter quarter. Oh, and I quickly prepped for an expedition to Nepal’s Rolwaling Valley and Ama Dablam. In case you missed it, check out the trip reports linked in the previous sentence and the new expedition video.

For a couple months I held my shit together. During September and October, I routinely logged 16 hour days settling her affairs, working on the house and getting ready for a move back west to return to Santa Clara full time for the winter quarter. Oh, and I quickly prepped for an expedition to Nepal’s Rolwaling Valley and Ama Dablam. In case you missed it, check out the trip reports linked in the previous sentence and the new expedition video. Then, during AGU, the largest earth science conference of the year (of course!), things changed. Instead of hopping on the train to San Francisco, I found myself shaking in the fetal position at home, my head racing. For the next few months, I was unable to focus on anything. Among other things, I became lost on the way to the grocery store, routinely sat in parking lots for hours on end trying to figure out if I needed to eat, drink or pee. Communication of all sorts was an enormous challenge. When people asked how things were going, I rarely knew how to respond. I tried to focus on the positives and use my time to work on things that made me happy like going for a walk, but often that was too daunting of an undertaking. Brewing with frustration, I routinely lost control and broke my things, often for reasons unknown to me even in the moment. I lost confidence in myself all of my abilities to work, be happy or contribute to my relationships. I wrote Mingma Gyalje and told him I might not be able to climb this summer. He told me he’d lost his father to intestine cancer and found himself slowly getting more hopeless and weaker. He told me he changed his routine, returned to trekking and climbing, shared moments with friends and gradually came back.

Then, during AGU, the largest earth science conference of the year (of course!), things changed. Instead of hopping on the train to San Francisco, I found myself shaking in the fetal position at home, my head racing. For the next few months, I was unable to focus on anything. Among other things, I became lost on the way to the grocery store, routinely sat in parking lots for hours on end trying to figure out if I needed to eat, drink or pee. Communication of all sorts was an enormous challenge. When people asked how things were going, I rarely knew how to respond. I tried to focus on the positives and use my time to work on things that made me happy like going for a walk, but often that was too daunting of an undertaking. Brewing with frustration, I routinely lost control and broke my things, often for reasons unknown to me even in the moment. I lost confidence in myself all of my abilities to work, be happy or contribute to my relationships. I wrote Mingma Gyalje and told him I might not be able to climb this summer. He told me he’d lost his father to intestine cancer and found himself slowly getting more hopeless and weaker. He told me he changed his routine, returned to trekking and climbing, shared moments with friends and gradually came back. Slowly things began to change. Michelle got me a watch to track my activities. Old interests like biking and gear-fondling re-emerged. I bought a Pivot, a gorgeous mountain bike just begging to climb the steep fire roads and rip singletrack descents in the Santa Cruz Mountains where Michelle and I had recently moved. At first I was self conscious about the purchase, but soon the freedom opened me up. But the epic rains of this past winter quickly put the trails out of commission, so I did the only logical thing I could think of: splurging on a ridiculously capable BMC road disc bike ready to hit the rough pavement and gravel climbs. Soon, I felt my complete self returning to form. My legs rounded into shape and my aerobic fitness skyrocketed. I could finally focus long enough to send an email. I could do the dishes, make the bed and fold laundry. The house in Virginia sold, and I finally wasn’t getting caught by daily legal and financial surprises in the mail for my mom and grandpa. I started to feel new emotions: gratitude for my privileged and rich life, the support of those around me, the freedom from Santa Clara to focus on my health, and a desire to get on with things. I was on my way.

Slowly things began to change. Michelle got me a watch to track my activities. Old interests like biking and gear-fondling re-emerged. I bought a Pivot, a gorgeous mountain bike just begging to climb the steep fire roads and rip singletrack descents in the Santa Cruz Mountains where Michelle and I had recently moved. At first I was self conscious about the purchase, but soon the freedom opened me up. But the epic rains of this past winter quickly put the trails out of commission, so I did the only logical thing I could think of: splurging on a ridiculously capable BMC road disc bike ready to hit the rough pavement and gravel climbs. Soon, I felt my complete self returning to form. My legs rounded into shape and my aerobic fitness skyrocketed. I could finally focus long enough to send an email. I could do the dishes, make the bed and fold laundry. The house in Virginia sold, and I finally wasn’t getting caught by daily legal and financial surprises in the mail for my mom and grandpa. I started to feel new emotions: gratitude for my privileged and rich life, the support of those around me, the freedom from Santa Clara to focus on my health, and a desire to get on with things. I was on my way.

Sea Level

This past weekend, a few friends and I caught up with my good friend Zach, who's currently on his way to Alaska the not-so-easy way. Part celebration (he just finished his PhD), part promotion for his dream to build and operate an earth system science experiential learning paradise near his home in southeast Alaska and part personal journey, Zach is walking from Stanford to Port Angeles, Washington, then kayaking the Inside Passage back home to Glacier Bay.

This past weekend, a few friends and I caught up with my good friend Zach, who's currently on his way to Alaska the not-so-easy way. Part celebration (he just finished his PhD), part promotion for his dream to build and operate an earth system science experiential learning paradise near his home in southeast Alaska and part personal journey, Zach is walking from Stanford to Port Angeles, Washington, then kayaking the Inside Passage back home to Glacier Bay.

We drove up to share a day on the trail together in northern California's fabled Lost Coast and bring him some much needed camping fuel (and leftover pizza!). You can follow his five-month journey at inianislandsinstitute.org and check in on Zach's exact whereabouts here.

We drove up to share a day on the trail together in northern California's fabled Lost Coast and bring him some much needed camping fuel (and leftover pizza!). You can follow his five-month journey at inianislandsinstitute.org and check in on Zach's exact whereabouts here.

More thankful than ever

I live a charmed life. Occasionally I’ll be stopped in my tracks when I stumble upon an old photo…was I really there? Did I actually drink fermented camel’s milk in Mongolia?!?This year, I have even more reason to be thankful. It’s also the main reason I haven’t posted in a while. Next year, I'll be an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Santa Clara University. It’s an absolute dream for me to make this next step, and I couldn’t be happier at the prospect of joining such a wonderful group of people.

I live a charmed life. Occasionally I’ll be stopped in my tracks when I stumble upon an old photo…was I really there? Did I actually drink fermented camel’s milk in Mongolia?!?This year, I have even more reason to be thankful. It’s also the main reason I haven’t posted in a while. Next year, I'll be an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Santa Clara University. It’s an absolute dream for me to make this next step, and I couldn’t be happier at the prospect of joining such a wonderful group of people. I wasn’t able to get out much this fall as I was super busy with the job search and PhD work. I also messed my ankle up really badly in late September. I’d never rolled my left ankle before but I tore pretty much everything. I’m in really good running shape now and lifting as well, but mountain trips were off limits this fall. I did sneak off to Yosemite Valley for a quick weekend with my good buddy Mike. He led all the hard pitches and I climbed pretty poorly but loved every minute. Found a great veggie burger and milkshake on the way home too…Hula’s in Escalon is tasty!

I wasn’t able to get out much this fall as I was super busy with the job search and PhD work. I also messed my ankle up really badly in late September. I’d never rolled my left ankle before but I tore pretty much everything. I’m in really good running shape now and lifting as well, but mountain trips were off limits this fall. I did sneak off to Yosemite Valley for a quick weekend with my good buddy Mike. He led all the hard pitches and I climbed pretty poorly but loved every minute. Found a great veggie burger and milkshake on the way home too…Hula’s in Escalon is tasty!

Everest’s neighbor: A case for Lhotse

Choosing the right objective is always a huge part of climbing. The bigger the peak, the bigger those considerations. Just on a practical level, if you’re going to commit a lot of effort and a couple months towards something, you should be happy about the idea. I’m climbing what many people would call an unusual mountain this spring—there’s not a lot of attention for Everest’s slightly shorter neighbor, so I’d like to let you in on what gets me excited about Lhotse.A crash course on the world’s highest mountainsThere are fourteen 8000m (26,200ish ft) peaks in the world. Obviously, just as with Colorado’s 14ers, it’s an arbitrary cutoff. Here’s the way the elevation and difficulty breakdown of the normal (commercialized in some cases) 8000er routes looks to me: …..big gap of nearly 1000 ft from Everest to K2…..

…..big gap of nearly 1000 ft from Everest to K2…..

…..big gap of nearly 1000 ft…..Cho Oyu through Shishapangma 8000ers #6-14 are between 8200m and 8000m and vary greatly in their difficulty, remoteness, and danger.I’m pointing this out because these really is an enormous physiological difference between 8000 and 8500m. When you add in the architectural differences of these peaks, this becomes even more obvious. For example, on Everest, you need to camp at nearly 8000m on the south side and most people “camp” at 8300m, higher than the world’s 6th highest mountain, on the north side.I’m interested in exploring a type of direct interaction with the mountains. Extremely high altitude certainly isn’t my only focus, far from it, but it is pretty wild up there. Just overcoming the apathy, staying calm, plugging away and just taking care of yourself (for potentially 7-8 weeks!) sounds like it could be up my alley. So this will be my first try.Why Lhotse? Well, first off, I wouldn’t be on this trip without the Extreme Environments - Everyday Decisions research project and some huge supporters, so thanks! I’m still just a grad student, and this is the first time I’ve taken a couple months of unpaid leave to make something happen. I definitely wouldn’t be on a peak this expensive with such a quality operation without a tremendous amount of help. If you want to see some of the organizations that have helped made this possible, check out the Partners page.So, in choosing a first 8000m peak, there are some patterns that you can see. A few 8000ers have been somewhat designated as good choices…Cho Oyu, the world’s 6th highest peak being a great example. Cho Oyu has become somewhat of a primer for Everest, and a lot of commercial clients are now getting guided up Cho in the fall before an Everest summit bid the next spring. Manaslu and Shishapangma have also seen a lot of commercial attention. All of these peaks are in that 8000-8200m bracket of elevation, and something like Cho Oyu is a very straightforward technical climb. As I’ve had a “good” time on some of my previous 7000m peaks and I’m going with a great deal of commercial support, I’m feeling confident enough to try a peak that’s a bit higher. This wouldn’t matter if I were using oxygen, but we’ll get to that. I also am really drawn to slightly steeper peaks for aesthetics and enjoyment of the movement. Even though I have fairly limited technical ability, I still want this to be more than a pure snow slog.Ok, the world’s five highest peaks:Everest…In a category of its own in a lot of ways. Without oxygen though, it’s a completely different beast, even compared to Lhotse. Honestly, climbing both Lhotse and Everest was on the table (at least in my head), but after talking with my expedition leader, Lhotse became the clear choice.K2 and Kangchenjunga…Not in play for first 8000m peaks for me. We all make our own rules in climbing, but those weren’t even a consideration. This was just an honest personal assessment about my experience and willingness to take risk. I realized that I don’t even know enough to break down how I would climb those two, even though its probably possible. The more important question is if it’s right, and I know it’s not. Both are too big, too hard, too remote and have a bunch of objective dangers that I don’t know enough about at this point.Lhotse…This was the obvious decision given that our project is to study commercial operations on Everest. This allows me to be in the same base camp, climb almost the entire normal route on Everest before deviating off to Lhotse on summit day. Also, given my limited resources, Everest would have been a huge financial commitment, and I just want to go climbing for two months.Makalu…Ok, I really really would have liked to try Makalu. If I enjoy myself this spring and have a good team I’d stay open the idea. Compared with Lhotse though, it would definitely be more remote and more difficult, so I’m probably doing this in a more controlled way as it is.Commercial MountaineeringI’m probably not going to do a bunch more commercial trips…certainly not big, pricey, full-service guided trips. If I do, I’ll probably take some degree of commercial logistical and base camp support like I did last summer in the Pamir, but choose to climb with peers. I think commercial mountaineering serves some great purposes for me though. I was told by a friend not to increase more than one variable at a time in climbing. I’m trying my best to stick to that, and the bottom line is that doing Lhotse with this degree of support in place makes it a much safer and more controlled experiment. I have a lot to learn, and it'll be great to be mentored for a while.Usually, I find that the more that my partners and I handle as teammates and peers, the more rewarding the experience. In this case, I guess I have enough respect for true modern alpinism that I’m dipping my toe in the waters before jumping in. When I do what I consider real alpinism, it’s usually on peaks that are much more firmly within what I see as my capabilities. I’ve only teased it in the big mountains. If it turns out I like it, hey, I’m young and the mountains will still be there.OxygenSo, I’m adding just one variable back in. Look, it’s 2013…there’s 3G cell service up there! I’m not forgoing amazing boots, refusing to get any route information, or plugging my ears when someone is reading off the latest custom weather forecast off the internet. And we will have oxygen available…I’ll be climbing with a sherpa on oxygen, who will have an extra for me in the event that I need it. I’m not saying going without, umm, air is a good idea, but we're definitely making compromises.

…..big gap of nearly 1000 ft…..Cho Oyu through Shishapangma 8000ers #6-14 are between 8200m and 8000m and vary greatly in their difficulty, remoteness, and danger.I’m pointing this out because these really is an enormous physiological difference between 8000 and 8500m. When you add in the architectural differences of these peaks, this becomes even more obvious. For example, on Everest, you need to camp at nearly 8000m on the south side and most people “camp” at 8300m, higher than the world’s 6th highest mountain, on the north side.I’m interested in exploring a type of direct interaction with the mountains. Extremely high altitude certainly isn’t my only focus, far from it, but it is pretty wild up there. Just overcoming the apathy, staying calm, plugging away and just taking care of yourself (for potentially 7-8 weeks!) sounds like it could be up my alley. So this will be my first try.Why Lhotse? Well, first off, I wouldn’t be on this trip without the Extreme Environments - Everyday Decisions research project and some huge supporters, so thanks! I’m still just a grad student, and this is the first time I’ve taken a couple months of unpaid leave to make something happen. I definitely wouldn’t be on a peak this expensive with such a quality operation without a tremendous amount of help. If you want to see some of the organizations that have helped made this possible, check out the Partners page.So, in choosing a first 8000m peak, there are some patterns that you can see. A few 8000ers have been somewhat designated as good choices…Cho Oyu, the world’s 6th highest peak being a great example. Cho Oyu has become somewhat of a primer for Everest, and a lot of commercial clients are now getting guided up Cho in the fall before an Everest summit bid the next spring. Manaslu and Shishapangma have also seen a lot of commercial attention. All of these peaks are in that 8000-8200m bracket of elevation, and something like Cho Oyu is a very straightforward technical climb. As I’ve had a “good” time on some of my previous 7000m peaks and I’m going with a great deal of commercial support, I’m feeling confident enough to try a peak that’s a bit higher. This wouldn’t matter if I were using oxygen, but we’ll get to that. I also am really drawn to slightly steeper peaks for aesthetics and enjoyment of the movement. Even though I have fairly limited technical ability, I still want this to be more than a pure snow slog.Ok, the world’s five highest peaks:Everest…In a category of its own in a lot of ways. Without oxygen though, it’s a completely different beast, even compared to Lhotse. Honestly, climbing both Lhotse and Everest was on the table (at least in my head), but after talking with my expedition leader, Lhotse became the clear choice.K2 and Kangchenjunga…Not in play for first 8000m peaks for me. We all make our own rules in climbing, but those weren’t even a consideration. This was just an honest personal assessment about my experience and willingness to take risk. I realized that I don’t even know enough to break down how I would climb those two, even though its probably possible. The more important question is if it’s right, and I know it’s not. Both are too big, too hard, too remote and have a bunch of objective dangers that I don’t know enough about at this point.Lhotse…This was the obvious decision given that our project is to study commercial operations on Everest. This allows me to be in the same base camp, climb almost the entire normal route on Everest before deviating off to Lhotse on summit day. Also, given my limited resources, Everest would have been a huge financial commitment, and I just want to go climbing for two months.Makalu…Ok, I really really would have liked to try Makalu. If I enjoy myself this spring and have a good team I’d stay open the idea. Compared with Lhotse though, it would definitely be more remote and more difficult, so I’m probably doing this in a more controlled way as it is.Commercial MountaineeringI’m probably not going to do a bunch more commercial trips…certainly not big, pricey, full-service guided trips. If I do, I’ll probably take some degree of commercial logistical and base camp support like I did last summer in the Pamir, but choose to climb with peers. I think commercial mountaineering serves some great purposes for me though. I was told by a friend not to increase more than one variable at a time in climbing. I’m trying my best to stick to that, and the bottom line is that doing Lhotse with this degree of support in place makes it a much safer and more controlled experiment. I have a lot to learn, and it'll be great to be mentored for a while.Usually, I find that the more that my partners and I handle as teammates and peers, the more rewarding the experience. In this case, I guess I have enough respect for true modern alpinism that I’m dipping my toe in the waters before jumping in. When I do what I consider real alpinism, it’s usually on peaks that are much more firmly within what I see as my capabilities. I’ve only teased it in the big mountains. If it turns out I like it, hey, I’m young and the mountains will still be there.OxygenSo, I’m adding just one variable back in. Look, it’s 2013…there’s 3G cell service up there! I’m not forgoing amazing boots, refusing to get any route information, or plugging my ears when someone is reading off the latest custom weather forecast off the internet. And we will have oxygen available…I’ll be climbing with a sherpa on oxygen, who will have an extra for me in the event that I need it. I’m not saying going without, umm, air is a good idea, but we're definitely making compromises. Not using oxygen is an enormous difference though. Check out the graph above from Tom Hornbein, an American Everest legend. Even if these numbers aren’t exactly right, it should give us some idea. These days, it’s pretty common for people to sleep on 0.5L/min starting over 7000m and on summit day, 2L/min is a common flow rate. Some climbers will even pay for extra bottles and use 4L/min. If these curves are in the ballpark, it basically could turn the summit of Everest into a 7000m peak, perhaps lower. So for me, even though using oxygen certainly would not be easy or a guaranteed summit, I'd like the opportunity to try something I genuinely don’t know if I can do.I’m not sure I have a very crystallized opinion of oxygen use in general, and it’d be pretty pointless for me to mouth off about it since I haven’t yet been on a peak high enough to warrant its use. With regards to my own personal use of supplementary oxygen, I feel that as long as the defining attribute of the route on Lhotse is that it’s very high, I should experience the mountain for what it is. That’s my feeling with all of my other climbs, from gazing up at Longs Peak as a child and wondering just how high it was and what it was like up there to now. I don’t want to sanitize the experience. I want direct interaction with the mountains, the naked vulnerable feeling of being out there more than I want to summit.A devil’s advocate argument typically follows. Something along the lines of, “Well, you’re wearing down, isn’t that an artificial advantage? Why not go with the clothes Mallory wore? Why not climb the Kangshung Face of Everest naked?” Well, I guess because I’m not arguing anything. One of the things I like most about the mountains is the sense of true freedom, and that all possibilities are open. There are of course, certain limitations. We must not harm the environment and our wild places. We must be fair to local peoples. But those answers are beyond the scope of this discussion. Be a good person. Do what you want to do. This is me.

Not using oxygen is an enormous difference though. Check out the graph above from Tom Hornbein, an American Everest legend. Even if these numbers aren’t exactly right, it should give us some idea. These days, it’s pretty common for people to sleep on 0.5L/min starting over 7000m and on summit day, 2L/min is a common flow rate. Some climbers will even pay for extra bottles and use 4L/min. If these curves are in the ballpark, it basically could turn the summit of Everest into a 7000m peak, perhaps lower. So for me, even though using oxygen certainly would not be easy or a guaranteed summit, I'd like the opportunity to try something I genuinely don’t know if I can do.I’m not sure I have a very crystallized opinion of oxygen use in general, and it’d be pretty pointless for me to mouth off about it since I haven’t yet been on a peak high enough to warrant its use. With regards to my own personal use of supplementary oxygen, I feel that as long as the defining attribute of the route on Lhotse is that it’s very high, I should experience the mountain for what it is. That’s my feeling with all of my other climbs, from gazing up at Longs Peak as a child and wondering just how high it was and what it was like up there to now. I don’t want to sanitize the experience. I want direct interaction with the mountains, the naked vulnerable feeling of being out there more than I want to summit.A devil’s advocate argument typically follows. Something along the lines of, “Well, you’re wearing down, isn’t that an artificial advantage? Why not go with the clothes Mallory wore? Why not climb the Kangshung Face of Everest naked?” Well, I guess because I’m not arguing anything. One of the things I like most about the mountains is the sense of true freedom, and that all possibilities are open. There are of course, certain limitations. We must not harm the environment and our wild places. We must be fair to local peoples. But those answers are beyond the scope of this discussion. Be a good person. Do what you want to do. This is me.

Alps Page Published

My first trip outside North America was to teach an earth science course in Europe. Afterwards, I made sure to visit the Tour de France and visit Chamonix, the home of alpinism, and Zermatt for an attempt on the Matterhorn. Full trip report here.

Shasta Trip Report Posted

One of my best days ever in the mountains was a winter solo of Shasta's Casaval Ridge. Full trip report and pictures here.

Text Dispatch: Moskvin Glacier, 14300ft

I was stranded in Jergatol for a few extra days due to Tajik dysfunctionality, but today I caught a lift on Tajikistans only chopper to base camp. This is the icy heart of the Pamir, surrounded by giants. The great Fedchenko Glacier, the longest outside the polar regions, lies just over the ridge. Peak Communism towers above. I'll have to go slowly again as I spent too long down low.

Himalaya Trip Report Added

My first expedition climb was a trip to Nepal in 2010. The climbing itself ended up being a pretty small portion of the three week trip, but my first trip to Asia was filled with adventure from start to finish. Some highlights from one of the world's magical places are here.

Text Dispatch: Camp 3, 20000ft

Safe in c3 after summit. Probably the hardest day I've had in the mountains. More to come.

Text Dispatch: Camp 3, 20000ft

One of the hardest days I've ever had. A stomach problem has left me drained physically and mentally. It continues to snow heavily. Today I stumbled up here through deep snow and whiteout conditions. Tom has the first chance to summit but I'm not sure if I will have the strength or health. Can't even see the world now. It's just rocks, snow, and this storm. Plants and people must be elsewhere.

Text Dispatch: Lenin Update

I think there was the first summit of the year today. After my rough first trip up the mtn I went to bc to recover and get the last of my summit gear. Boris went to c3 and is now going to bc to rest. I'm back up at c2 and headed up tomorrow. I'm climbing with Ishmael and Rufat, experienced and kind guys from Azerbaijan. With good weather and health we may try for the summit as early as the 19th.