A mini piggyback

I'm back to my usual summer pattern of getting into my research while simultaneously disappearing into the mountains for a while. This summer's travels started with a mini "piggyback" - a combo research and field adventure. This time, Sean and I headed to San Diego to give a talk and have some meetings at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scripps is filled with bright and energetic people who somehow manage to get work done despite their idyllic setting.

I'm back to my usual summer pattern of getting into my research while simultaneously disappearing into the mountains for a while. This summer's travels started with a mini "piggyback" - a combo research and field adventure. This time, Sean and I headed to San Diego to give a talk and have some meetings at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scripps is filled with bright and energetic people who somehow manage to get work done despite their idyllic setting. After a few days of productive discussion, we headed north to the Eastern Sierra. Aiming for some alpine rock routes in the Whitney region, we shouldered packs with a few days of supplies and headed up the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek.

After a few days of productive discussion, we headed north to the Eastern Sierra. Aiming for some alpine rock routes in the Whitney region, we shouldered packs with a few days of supplies and headed up the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek.

Unfortunately, morning showers and even stronger afternoon thunderstorms prevented us from getting on any of the technical routes, but it was a great trip nonetheless.

Unfortunately, morning showers and even stronger afternoon thunderstorms prevented us from getting on any of the technical routes, but it was a great trip nonetheless.

Chasing Neutrons

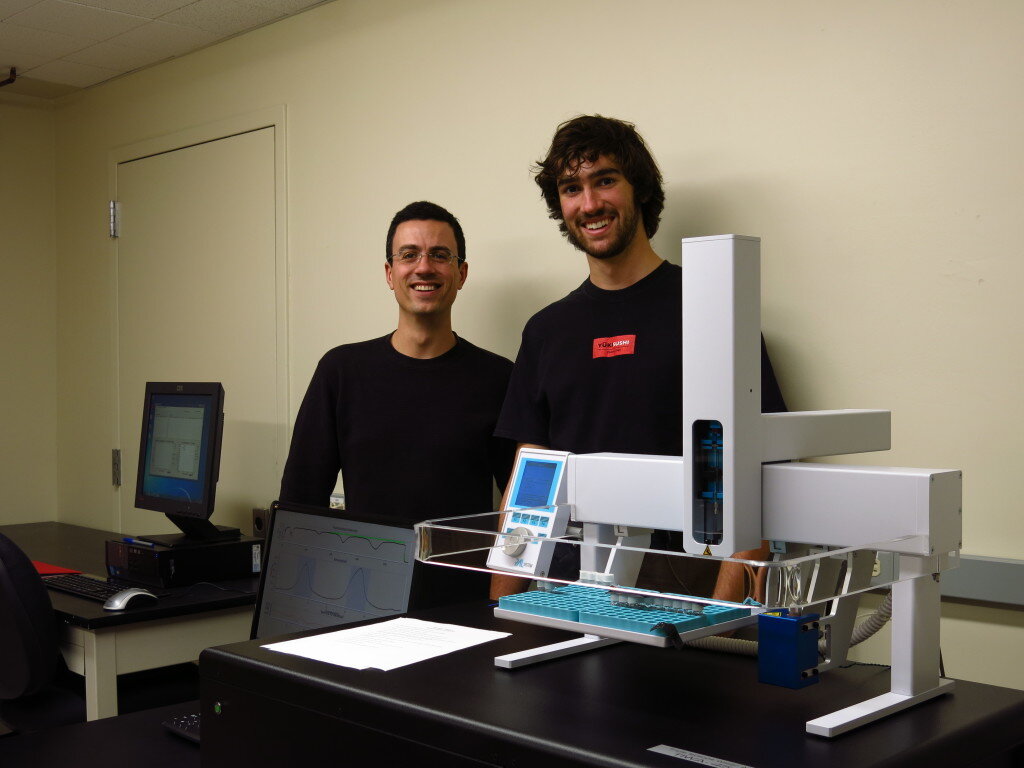

Ask any tenured or tenure-track professor about their first year and you're bound to get a seasoned, almost gleeful look in return. "Just wait a few years, it'll get easier," they'll say, as they recount the desperate sprint of starting out as a faculty member.A few months into my first year, I can officially report that faculty life presents a daunting set of challenges. And I've had it easy: no cross country move, no job search for a spouse, no young children to raise. But while the honeymoon years of infinite intellectual and recreational freedom that defined my graduate career have come and gone (hey, the pictures on this blog didn't take themselves!), I gaze out at the landscape of opportunities ahead.Lately, I've been coming to terms with the contrast between the countless problems I can work on and the startlingly short horizon defining the frontier of my knowledge and skills. Part of what's made the job so all-consuming have been the strategic questions, the big upfront decisions I make that will shape my research trajectory over the coming years. Not to mention figuring out how these "work" decisions will ultimately fit into a happy and fulfilling life. First step, many a scientist's rite of passage, building my own lab...

Ask any tenured or tenure-track professor about their first year and you're bound to get a seasoned, almost gleeful look in return. "Just wait a few years, it'll get easier," they'll say, as they recount the desperate sprint of starting out as a faculty member.A few months into my first year, I can officially report that faculty life presents a daunting set of challenges. And I've had it easy: no cross country move, no job search for a spouse, no young children to raise. But while the honeymoon years of infinite intellectual and recreational freedom that defined my graduate career have come and gone (hey, the pictures on this blog didn't take themselves!), I gaze out at the landscape of opportunities ahead.Lately, I've been coming to terms with the contrast between the countless problems I can work on and the startlingly short horizon defining the frontier of my knowledge and skills. Part of what's made the job so all-consuming have been the strategic questions, the big upfront decisions I make that will shape my research trajectory over the coming years. Not to mention figuring out how these "work" decisions will ultimately fit into a happy and fulfilling life. First step, many a scientist's rite of passage, building my own lab...

I'm also continuing to refine the "piggyback," where a work trip incorporates a bit of play. Case in point, spring break was spent with my student researcher Sean, who just happens to be a superb rock climber (wink). Read more of Sean's exploits here. So we dropped by Yosemite valley for a couple days on the way out to fieldwork in the Eastern Sierra near Reno. I gladly gave Sean all the runout pitches on valley classics including Snake Dike, the legendary line on Half Dome. Hiking out, I noticed a scratchy throat and proceeded to get violently sick for the rest of break and the next couple weeks, but all in all, it was a very successful trip sampling and otherwise.

I'm also continuing to refine the "piggyback," where a work trip incorporates a bit of play. Case in point, spring break was spent with my student researcher Sean, who just happens to be a superb rock climber (wink). Read more of Sean's exploits here. So we dropped by Yosemite valley for a couple days on the way out to fieldwork in the Eastern Sierra near Reno. I gladly gave Sean all the runout pitches on valley classics including Snake Dike, the legendary line on Half Dome. Hiking out, I noticed a scratchy throat and proceeded to get violently sick for the rest of break and the next couple weeks, but all in all, it was a very successful trip sampling and otherwise.

Oh, and I'll get back up in the big mountains too...I'm just shaking out before the crux!P.S. Thanks to everyone who's reached out to me with regards to the Nepal earthquake. Lots of friends over there have been affected, but luckily a lot of the news I'm getting from the ground now is better than I'd feared. Still many are in need. For those who've been asking, I've been recommending the American Himalayan Foundation as a great organization on the ground that's currently directing 100% of donations to relief and long term recovery in Nepal.P.P.S. A few years ago, I came across a couple mountain guides from Oregon who snapped these awesome shots of me in action on Bugaboo Spire in BC. Somehow my email address was temporarily lost, but look what came in the mail!

Oh, and I'll get back up in the big mountains too...I'm just shaking out before the crux!P.S. Thanks to everyone who's reached out to me with regards to the Nepal earthquake. Lots of friends over there have been affected, but luckily a lot of the news I'm getting from the ground now is better than I'd feared. Still many are in need. For those who've been asking, I've been recommending the American Himalayan Foundation as a great organization on the ground that's currently directing 100% of donations to relief and long term recovery in Nepal.P.P.S. A few years ago, I came across a couple mountain guides from Oregon who snapped these awesome shots of me in action on Bugaboo Spire in BC. Somehow my email address was temporarily lost, but look what came in the mail!

What can clay tell us about the past?

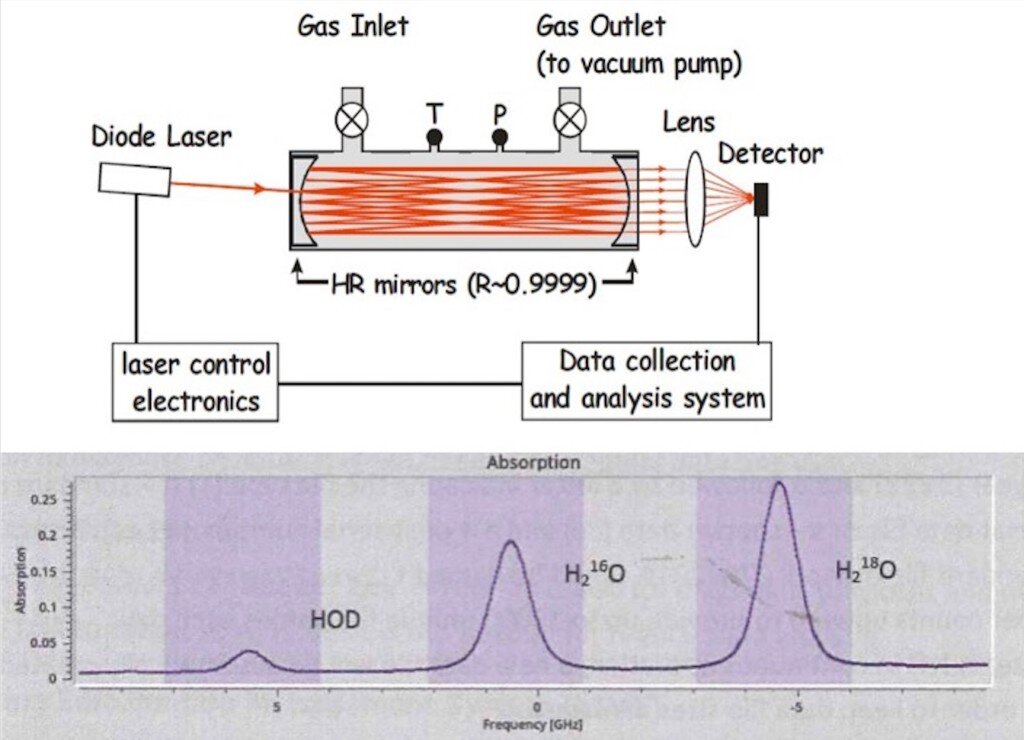

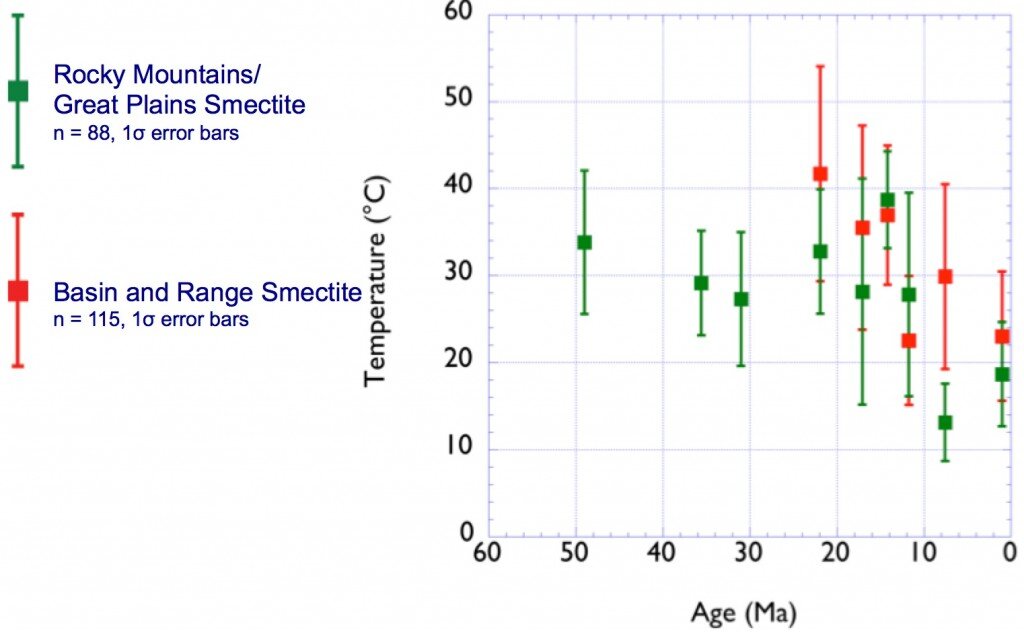

How hot was it in Colorado yesterday? Ok, how about 20 million years ago? Hmm, that one seems trickier to answer. I recently took a stab at this and other questions in North American paleoclimate in the final chapter of my PhD, which has been accepted in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, a leading geochemistry journal. I've been somewhat reluctant to write about this as it's not exactly the most accessible work I've done, plus I've been trying to run away from the last remaining scraps of my PhD in search of fresh research topics!Anyhow, here's a go at some of what I've been working on since 2008. Telling the conditions in the geologic past has always been challenging, but our foundation of knowledge has always been observational science. For many decades, paleontologists have studied fossils to determine information about ancient climate and environments. One metric involves analyzing the shapes of leaves, then using statistical models to determine things such as ancient temperature and rainfall. I belong to a community of scientists who use the chemistry of ancient sediments to learn about the past. Harold Urey's discovery of deuterium (hydrogen with an extra neutron) not only won him the Nobel Prize in 1934, but also gave birth to an entire field of stable isotope paleoclimatology. As it turns out, many natural processes preferentially take one isotope (forms of an element with different masses) over another in what is known as isotopic fractionation. For example, photosynthesis preferentially uses "light" carbon-12 in CO₂ over the heavier carbon-13. One of the best things from a climate standpoint, though, is that most isotopic fractionation is temperature dependent, meaning that we can calculate temperature if we know some more things about the system. Most famously, our best records of climate change over geologic timescales come from ancient fossils of tiny foraminifera buried in ocean sediments. The chemistry of their shells, made out of calcium carbonate, tells us about the temperature and amount of ice on the ancient earth.Here's where the clay comes in...clay minerals form as weathering products in soils. The clay forms in equilibrium with ancient water, and preserves the ancient isotopic signatures of oxygen and hydrogen, allowing us to study the ancient climate. I've been using the peculiar chemistry of smectite, a particular type of clay that weathered out of volcanic ash from enormous eruptions to tell the temperature history of western North America.

I belong to a community of scientists who use the chemistry of ancient sediments to learn about the past. Harold Urey's discovery of deuterium (hydrogen with an extra neutron) not only won him the Nobel Prize in 1934, but also gave birth to an entire field of stable isotope paleoclimatology. As it turns out, many natural processes preferentially take one isotope (forms of an element with different masses) over another in what is known as isotopic fractionation. For example, photosynthesis preferentially uses "light" carbon-12 in CO₂ over the heavier carbon-13. One of the best things from a climate standpoint, though, is that most isotopic fractionation is temperature dependent, meaning that we can calculate temperature if we know some more things about the system. Most famously, our best records of climate change over geologic timescales come from ancient fossils of tiny foraminifera buried in ocean sediments. The chemistry of their shells, made out of calcium carbonate, tells us about the temperature and amount of ice on the ancient earth.Here's where the clay comes in...clay minerals form as weathering products in soils. The clay forms in equilibrium with ancient water, and preserves the ancient isotopic signatures of oxygen and hydrogen, allowing us to study the ancient climate. I've been using the peculiar chemistry of smectite, a particular type of clay that weathered out of volcanic ash from enormous eruptions to tell the temperature history of western North America. My study involved collected hundreds of samples of weathered ash from all over western North America, with ages ranging from 620,000 years to about 30 million years. I separated the clay minerals using a centrifuge (read: lots of dishwashing!) and analyzed the oxygen and hydrogen isotope composition using mass spectrometry.

My study involved collected hundreds of samples of weathered ash from all over western North America, with ages ranging from 620,000 years to about 30 million years. I separated the clay minerals using a centrifuge (read: lots of dishwashing!) and analyzed the oxygen and hydrogen isotope composition using mass spectrometry. What do our results say? Well, quite a few things, but temperatures in North America follow global prevailing trends. It was quite a lot warmer (~10-15 degrees C) around 15 million years ago at a time known as the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. This was the most recent time of elevated global temperatures similar to where we may be headed by 2100 with modern climate change. If my results are any indication, continental interiors may warm to a greater degree than global averages.

What do our results say? Well, quite a few things, but temperatures in North America follow global prevailing trends. It was quite a lot warmer (~10-15 degrees C) around 15 million years ago at a time known as the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. This was the most recent time of elevated global temperatures similar to where we may be headed by 2100 with modern climate change. If my results are any indication, continental interiors may warm to a greater degree than global averages.

Rising mountains dried out Central Asia

Something has come of those two summers spent bouncing around Mongolia in Russian vans! Work led by my fellow grad student and travel companion Jeremy Caves has been presented, submitted for publication, and picked up by a few science news aggregators. This piece, written by Stanford's earth science writer Ker Than, puts some of our findings into English...-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rising mountains dried out Central AsiaA record of ancient rainfall teased from long-buried sediments in Mongolia is challenging the popular idea that the arid conditions prevalent in Central Asia today were caused by the ancient uplift of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau.Instead, Stanford scientists say the formation of two lesser mountain ranges, the Hangay and the Altai, may have been the dominant drivers of climate in the region, leading to the expansion of Asia's largest desert, the Gobi. The findings will be presented on Thursday, Dec. 12, at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco."These results have major implications for understanding the dominant factors behind modern-day Central Asia's extremely arid climate and the role of mountain ranges in altering regional climate," said Page Chamberlain, a professor of environmental Earth system science at Stanford.

Something has come of those two summers spent bouncing around Mongolia in Russian vans! Work led by my fellow grad student and travel companion Jeremy Caves has been presented, submitted for publication, and picked up by a few science news aggregators. This piece, written by Stanford's earth science writer Ker Than, puts some of our findings into English...-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rising mountains dried out Central AsiaA record of ancient rainfall teased from long-buried sediments in Mongolia is challenging the popular idea that the arid conditions prevalent in Central Asia today were caused by the ancient uplift of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau.Instead, Stanford scientists say the formation of two lesser mountain ranges, the Hangay and the Altai, may have been the dominant drivers of climate in the region, leading to the expansion of Asia's largest desert, the Gobi. The findings will be presented on Thursday, Dec. 12, at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco."These results have major implications for understanding the dominant factors behind modern-day Central Asia's extremely arid climate and the role of mountain ranges in altering regional climate," said Page Chamberlain, a professor of environmental Earth system science at Stanford. Scientists previously thought that the formation of the Himalayan mountain range and the Tibetan plateau around 45 million years ago shaped Asia's driest environments."The traditional explanation has been that the uplift of the Himalayas blocked air from the Indian Ocean from reaching central Asia," said Jeremy Caves, a doctoral student in Chamberlain's terrestrial paleoclimate research group who was involved in the study.

Scientists previously thought that the formation of the Himalayan mountain range and the Tibetan plateau around 45 million years ago shaped Asia's driest environments."The traditional explanation has been that the uplift of the Himalayas blocked air from the Indian Ocean from reaching central Asia," said Jeremy Caves, a doctoral student in Chamberlain's terrestrial paleoclimate research group who was involved in the study. This process was thought to have created a distinct rain shadow that led to wetter climates in India and Nepal and drier climates in Central Asia. Similarly, the elevation of the Tibetan Plateau was thought to have triggered an atmospheric process called subsidence, in which a mass of air heated by a high elevation slowly sinks into Central Asia."The falling air suppresses convective systems such as thunderstorms, and the result is you get really dry environments," Caves said.This long-accepted model of how Central Asia's arid environments were created mostly ignores, however, the existence of the Altai and Hangay, two northern mountain ranges.Searching for answersTo investigate the effects of the smaller ranges on the regional climate, Caves and his colleagues from Stanford and Rocky Mountain College in Montana traveled to Mongolia in 2011 and 2012 and collected samples of ancient soil, as well as stream and lake sediments from remote sites in the central, southwestern and western parts of the country.The team carefully chose its sites by scouring the scientific literature for studies of the region conducted by pioneering researchers in past decades."A lot of the papers were by Polish and Russian scientists who went there to look for dinosaur fossils," said Hari Mix, a doctoral student at Stanford who also participated in the research. "Indeed, at many of the sites we visited, there were dinosaur fossils just lying around."The earlier researchers recorded the ages and locations of the rocks they excavated as part of their own investigations; Caves and his team used those age estimates to select the most promising sites for their own study.At each site, the team bagged sediment samples that were later analyzed to determine their carbon isotope content. The relative level of carbon isotopes present in a soil sample is related to the productivity of plants growing in the soil, which is itself dependent on the annual rainfall. Thus, by measuring carbon isotope amounts from different sediment samples of different ages, the team was able to reconstruct past precipitation levels.An ancient wet periodThe new data suggest that rainfall in central and southwestern Mongolia had decreased by 50 to 90 percent in the last several tens of million of years."Right now, precipitation in Mongolia is about 5 inches annually," Caves said. "To explain our data, rainfall had to decrease from 10 inches a year or more to its current value over the last 10 to 30 million years."That means that much of Mongolia and Central Asia were still relatively wet even after the formation of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau 45 million years ago. The data show that it wasn't until about 30 million years ago, when the Hangay Mountains first formed, that rainfall started to decrease. The region began drying out even faster about 5 million to 10 million years ago, when the Altai Mountains began to rise.The scientists hypothesize that once they formed, the Hangay and Altai ranges created rain shadows of their own that blocked moisture from entering Central Asia."As a result, the northern and western sides of these ranges are wet, while the southern and eastern sides are dry," Caves said.The team is not discounting the effect of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau entirely, because portions of the Gobi Desert likely already existed before the Hangay or Altai began forming."What these smaller mountains did was expand the Gobi north and west into Mongolia," Caves said.The uplift of the Hangay and Altai may have had other, more far-reaching implications as well, Caves said. For example, westerly winds in Asia slam up against the Altai today, creating strong cyclonic winds in the process. Under the right conditions, the cyclones pick up large amounts of dust as they snake across the Gobi Desert. That dust can be lofted across the Pacific Ocean and even reach California, where it serves as microscopic seeds for developing raindrops.The origins of these cyclonic winds, as well as substantial dust storms in China today, may correlate with uplift of the Altai, Caves said. His team plans to return to Mongolia and Kazakhstan next summer to collect more samples and to use climate models to test whether the Altai are responsible for the start of the large dust storms."If the Altai are a key part of regulating Central Asia's climate, we can go and look for evidence of it in the past," Caves said.

This process was thought to have created a distinct rain shadow that led to wetter climates in India and Nepal and drier climates in Central Asia. Similarly, the elevation of the Tibetan Plateau was thought to have triggered an atmospheric process called subsidence, in which a mass of air heated by a high elevation slowly sinks into Central Asia."The falling air suppresses convective systems such as thunderstorms, and the result is you get really dry environments," Caves said.This long-accepted model of how Central Asia's arid environments were created mostly ignores, however, the existence of the Altai and Hangay, two northern mountain ranges.Searching for answersTo investigate the effects of the smaller ranges on the regional climate, Caves and his colleagues from Stanford and Rocky Mountain College in Montana traveled to Mongolia in 2011 and 2012 and collected samples of ancient soil, as well as stream and lake sediments from remote sites in the central, southwestern and western parts of the country.The team carefully chose its sites by scouring the scientific literature for studies of the region conducted by pioneering researchers in past decades."A lot of the papers were by Polish and Russian scientists who went there to look for dinosaur fossils," said Hari Mix, a doctoral student at Stanford who also participated in the research. "Indeed, at many of the sites we visited, there were dinosaur fossils just lying around."The earlier researchers recorded the ages and locations of the rocks they excavated as part of their own investigations; Caves and his team used those age estimates to select the most promising sites for their own study.At each site, the team bagged sediment samples that were later analyzed to determine their carbon isotope content. The relative level of carbon isotopes present in a soil sample is related to the productivity of plants growing in the soil, which is itself dependent on the annual rainfall. Thus, by measuring carbon isotope amounts from different sediment samples of different ages, the team was able to reconstruct past precipitation levels.An ancient wet periodThe new data suggest that rainfall in central and southwestern Mongolia had decreased by 50 to 90 percent in the last several tens of million of years."Right now, precipitation in Mongolia is about 5 inches annually," Caves said. "To explain our data, rainfall had to decrease from 10 inches a year or more to its current value over the last 10 to 30 million years."That means that much of Mongolia and Central Asia were still relatively wet even after the formation of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau 45 million years ago. The data show that it wasn't until about 30 million years ago, when the Hangay Mountains first formed, that rainfall started to decrease. The region began drying out even faster about 5 million to 10 million years ago, when the Altai Mountains began to rise.The scientists hypothesize that once they formed, the Hangay and Altai ranges created rain shadows of their own that blocked moisture from entering Central Asia."As a result, the northern and western sides of these ranges are wet, while the southern and eastern sides are dry," Caves said.The team is not discounting the effect of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau entirely, because portions of the Gobi Desert likely already existed before the Hangay or Altai began forming."What these smaller mountains did was expand the Gobi north and west into Mongolia," Caves said.The uplift of the Hangay and Altai may have had other, more far-reaching implications as well, Caves said. For example, westerly winds in Asia slam up against the Altai today, creating strong cyclonic winds in the process. Under the right conditions, the cyclones pick up large amounts of dust as they snake across the Gobi Desert. That dust can be lofted across the Pacific Ocean and even reach California, where it serves as microscopic seeds for developing raindrops.The origins of these cyclonic winds, as well as substantial dust storms in China today, may correlate with uplift of the Altai, Caves said. His team plans to return to Mongolia and Kazakhstan next summer to collect more samples and to use climate models to test whether the Altai are responsible for the start of the large dust storms."If the Altai are a key part of regulating Central Asia's climate, we can go and look for evidence of it in the past," Caves said.

Did Grassland Expansion affect North American Climate?

A major component of my graduate work is out in this month's Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Here's an attempt to translate some of what I think about into English...bear with me because I simply can't spend the time to cover enough background material. Some of these are actual figures so sorry for the compexity. The first chapter of my graduate work involved compiling and analyzing all of the existing records of climate change in western North America. Our research was motivated by the need to understand the topographic evolution of the Rocky Mountains and their effects on climate. My research group, along with several dozen other groups around the world, collects records of ancient climate using the chemistry of sedimentary rocks. By analyzing the ratios of isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen in particular minerals such as calcium carbonate, mica, clays, hydrated volcanic glass, and even fossil mammal teeth, we can decipher the climatic conditions of the past.

The first chapter of my graduate work involved compiling and analyzing all of the existing records of climate change in western North America. Our research was motivated by the need to understand the topographic evolution of the Rocky Mountains and their effects on climate. My research group, along with several dozen other groups around the world, collects records of ancient climate using the chemistry of sedimentary rocks. By analyzing the ratios of isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen in particular minerals such as calcium carbonate, mica, clays, hydrated volcanic glass, and even fossil mammal teeth, we can decipher the climatic conditions of the past.

One of the things we noticed during this work was a variety of explanations for stable isotope paleoclimate records in the last 20 or so million years. Nearly all of the records, except those in the rainshadow of the Cascade Mountains, increase in the amount of oxygen-18 in ancient precipitation. Over the last several years, I've worked on solving a set of questions exploring the possible contributions of grasslands to this climate change.

Despite the 3.7 billion year history of plants on Earth, the development of grasslands happened quite recently in the geological past, with grass-dominated landscapes appearing in North America over the last 25 or so million years. Grasslands rapidly expanded to their current extent (roughly 30% of Earth's land surface) mostly in the last 15 million years, coincident with global cooling, aridification and an increasingly seasonal climate. We figured that an ecological transition this large must have been accompanied by corresponding changes in climate. Plants recycle water through evapotranspiration...they all take in water from their roots and lose water through their leaves during photosynthesis. This effect is so great, some regions can practically create their own rainfall. Though grasses transpire less water than forests, they recycle more relative to the amount of precipitation in their region.

To test the idea that the rise of grass-dominated landscapes could have dramatically changed North American climate, we built a model to gain a mechanistic understanding of how different vegetation types would recycle water and affect climate downstream. In short, our findings were that grasslands indeed could have produced some of the most profound changes in climate and ushered in the modern climatic regime.

On the road (again)...and Generation Anthropocene Interview

Greetings from British Columbia! I've been out doing fieldwork with my research group. We're all collecting samples that will help constrain the climate in western North America during the particularly hot and humid Eocene (33-55 million years ago). We're visiting some of the most amazing plant fossil sites on the continent and collecting samples for our isotopic work. The fishing is amazing, both for us and the bald eagles. Bugs aren't (so) bad.A few weeks ago, I sat down with Generation Anthropocene, a podcast started by fellow Stanford students Michael Osborne, Miles Traer and Leslie Chang that confronts the reality that we, humans, are a force driving global-scale change. In the first ever two-part GenAnthro conversation, Miles, Leslie and I discuss mountains, science and beyond in a somewhat biographical piece:Part OnePart Two

Greetings from British Columbia! I've been out doing fieldwork with my research group. We're all collecting samples that will help constrain the climate in western North America during the particularly hot and humid Eocene (33-55 million years ago). We're visiting some of the most amazing plant fossil sites on the continent and collecting samples for our isotopic work. The fishing is amazing, both for us and the bald eagles. Bugs aren't (so) bad.A few weeks ago, I sat down with Generation Anthropocene, a podcast started by fellow Stanford students Michael Osborne, Miles Traer and Leslie Chang that confronts the reality that we, humans, are a force driving global-scale change. In the first ever two-part GenAnthro conversation, Miles, Leslie and I discuss mountains, science and beyond in a somewhat biographical piece:Part OnePart Two

Environmental and Geological Field Studies in the Rockies!

Complete photos here:SoCo 2012 Following the intense summer trip, I was happy to get back outside for one of my favorite trips. Every September, I help teach a field course for sophomores. My advisor, Page Chamberlain, has been leading these trips for 25 years. Still culture-shocked and with a lot to chew on after my Mongolia and Pamir expedition, I drove out with several other teaching assistants from California to Salt Lake where our trip begins.

Still culture-shocked and with a lot to chew on after my Mongolia and Pamir expedition, I drove out with several other teaching assistants from California to Salt Lake where our trip begins.

The trip goes by in thirds. During the first week, we hiked in to a base camp in the Wind River Range and taught orienteering, geologic mapping, early earth history and the carbon cycle.

The trip goes by in thirds. During the first week, we hiked in to a base camp in the Wind River Range and taught orienteering, geologic mapping, early earth history and the carbon cycle.

During the second portion of the trip, we camped in Grand Teton National Park, and studied stream chemistry, plate tectonics and the evolution of western North America. We spent a few days doing roadside geology in Yellowstone.

During the second portion of the trip, we camped in Grand Teton National Park, and studied stream chemistry, plate tectonics and the evolution of western North America. We spent a few days doing roadside geology in Yellowstone. I also managed to squeeze in a couple fun, easy climbs in the Tetons during our short break in Jackson. First, I headed with Dan, who'd climbed the Grand Teton last year with me, and Jake up Cube Point above Jenny Lake.

I also managed to squeeze in a couple fun, easy climbs in the Tetons during our short break in Jackson. First, I headed with Dan, who'd climbed the Grand Teton last year with me, and Jake up Cube Point above Jenny Lake. The next day, Annalisa and I got an early start to climb Teewinot Mountain. In the crisp darkness, we hiked between herds of bugling elk, before alpenglow lit up the world around us. As we ascended, we left the awful smoke from the many nearby fires. A few hours of climbing and scrambling on steep but clean rock brought us to Teewinot's summit...such a small perch beneath the Grand Teton and Mount Owen that only one of us could stand on top at once.

The next day, Annalisa and I got an early start to climb Teewinot Mountain. In the crisp darkness, we hiked between herds of bugling elk, before alpenglow lit up the world around us. As we ascended, we left the awful smoke from the many nearby fires. A few hours of climbing and scrambling on steep but clean rock brought us to Teewinot's summit...such a small perch beneath the Grand Teton and Mount Owen that only one of us could stand on top at once.

The last part of the trip has historically gone to the rough miner town of Cooke City, MT, just outside of Yellowstone, but this year we tried something new. The group went to the Sage Creek Basin in southwestern Montana to see the type of research we do. We ended up going to several areas we've studied in the past, and students helped collect samples that will contribute to our ongoing efforts to better constrain the history of climate and topography in North America.

The last part of the trip has historically gone to the rough miner town of Cooke City, MT, just outside of Yellowstone, but this year we tried something new. The group went to the Sage Creek Basin in southwestern Montana to see the type of research we do. We ended up going to several areas we've studied in the past, and students helped collect samples that will contribute to our ongoing efforts to better constrain the history of climate and topography in North America.

And as always, we brought instruments and played some good music. It was so wonderful to get some time to camp in a less stressful setting than this summer with a great group of TAs and students. Thanks guys!

Mongolia Part 2: To the Altai and Back

Complete pictures here:Very Best of Mongolia 2012On the summer solstice, we pressed on to the west, reaching Naran Daats Bulag, a spring in the western part of the Nemegt Basin. We camped on the small patch of green grass below the spring and next to a beautiful monument to Tengri, the sky god. The next day, we sampled the stratigraphic sections making up the cliffs around a large dry wash, and the day after traveled west to Tsagan Khushu before hitting the road towards the Altai.

The next day, we sampled the stratigraphic sections making up the cliffs around a large dry wash, and the day after traveled west to Tsagan Khushu before hitting the road towards the Altai. About an hour into the most rugged and remote driving in the trip, Tsele hit a shrub and got a flat. Changing the flat, in this case, involved also changing the inner tube, which required running over the tire with the Russian van to unseat it from the rim. We all took turns hand pumping the tire up to a million psi (don’t ask) in a massive sandstorm. Soon thereafter, Jobe started feeling bad from the heat and a stomach bug.

About an hour into the most rugged and remote driving in the trip, Tsele hit a shrub and got a flat. Changing the flat, in this case, involved also changing the inner tube, which required running over the tire with the Russian van to unseat it from the rim. We all took turns hand pumping the tire up to a million psi (don’t ask) in a massive sandstorm. Soon thereafter, Jobe started feeling bad from the heat and a stomach bug. Our Land Cruiser began deteriorating in a pretty serious way as we drove towards Shinejinst, the first town in several hundred miles. We could hardly make it up even the most trivial of inclines. By the time we reached Bayan-Ombor, things were very grim. The drivers had tried their best at repairing the vehicle in the field, and by repair, I mean busting a hole in the exhaust with our rock hammers, then welding it back together. Derek, who knows a ton about cars, correctly diagnosed the problem as being a clogged fuel filter almost as early as UB, but apparently banging on the muffler was the Mongolian tactic.

Our Land Cruiser began deteriorating in a pretty serious way as we drove towards Shinejinst, the first town in several hundred miles. We could hardly make it up even the most trivial of inclines. By the time we reached Bayan-Ombor, things were very grim. The drivers had tried their best at repairing the vehicle in the field, and by repair, I mean busting a hole in the exhaust with our rock hammers, then welding it back together. Derek, who knows a ton about cars, correctly diagnosed the problem as being a clogged fuel filter almost as early as UB, but apparently banging on the muffler was the Mongolian tactic.

The next day, it was decided that Tsele and the Land Cruiser would get towed several days back to Ulaanbaatar, while the rest of us piled in the Russian van and pressed on to the west. All seven of us along with our field gear bounced for a day to Biger.

The next day, it was decided that Tsele and the Land Cruiser would get towed several days back to Ulaanbaatar, while the rest of us piled in the Russian van and pressed on to the west. All seven of us along with our field gear bounced for a day to Biger. The next morning, to our elation, Nyamsakhin, our new driver, met us after rushing out from Bayanhongor in a day. With his deep voice, commanding yet laid back presence and general competence, we all joked that he was some type of mob boss in Bayanhongor. It turns out that he’s a bus driver, photography enthusiast and all-around awesome guy. Over the next few days, he would lead us on wild offroad chases of pohoon and tseg, antelope-like creatures who could outrun us at over 60 mph!

The next morning, to our elation, Nyamsakhin, our new driver, met us after rushing out from Bayanhongor in a day. With his deep voice, commanding yet laid back presence and general competence, we all joked that he was some type of mob boss in Bayanhongor. It turns out that he’s a bus driver, photography enthusiast and all-around awesome guy. Over the next few days, he would lead us on wild offroad chases of pohoon and tseg, antelope-like creatures who could outrun us at over 60 mph!

The stratigraphy in Biger was amazing. Hundreds of meters of sands, clays and gravels were perfectly laid out up a mountainside. By the time we finished at Biger, we knew the trip was going to be quite successful from a scientific standpoint. Jeremy certainly has enough samples for a PhD.

In Altay, we took our only rest day of the trip. While we’d essentially already planned on taking the day off, the Russian van needed a new rear differential. We took cold showers and played some basketball, which is quite popular in Monoglia. Often, you’ll see handmade wooden hoops outside gers.

In Altay, we took our only rest day of the trip. While we’d essentially already planned on taking the day off, the Russian van needed a new rear differential. We took cold showers and played some basketball, which is quite popular in Monoglia. Often, you’ll see handmade wooden hoops outside gers. A few days later and we were at our westernmost section at Dzereg. Once again, the sections were fantastic, but the only previous research into the western basins was horrendous. We had some running jokes and choice commentary for the previous authors, who among other things, had assigned an Oligocene (23-33 million year) age to sediments in Dariv purely based on their red color. After five minutes of walking around, Derek, who had done his master’s work in the basin, found a huge dinosaur fossil, confirming that the sediments were in fact Jurassic. Fieldwork is definitely complicated and making mistakes is understandable, but it’s best not to be off by over 100 million years. In Dzereg, an outcrop was described as an angular unconformity, or a gap in time, but the composition and orientation of the beds didn’t change at all. Yikes! I'd imagine some more tactful and professional responses will eventually make it into publication over the next few years.

A few days later and we were at our westernmost section at Dzereg. Once again, the sections were fantastic, but the only previous research into the western basins was horrendous. We had some running jokes and choice commentary for the previous authors, who among other things, had assigned an Oligocene (23-33 million year) age to sediments in Dariv purely based on their red color. After five minutes of walking around, Derek, who had done his master’s work in the basin, found a huge dinosaur fossil, confirming that the sediments were in fact Jurassic. Fieldwork is definitely complicated and making mistakes is understandable, but it’s best not to be off by over 100 million years. In Dzereg, an outcrop was described as an angular unconformity, or a gap in time, but the composition and orientation of the beds didn’t change at all. Yikes! I'd imagine some more tactful and professional responses will eventually make it into publication over the next few years. On our last day in Dzereg, we drove into town to see their Nadaam, the most important festival of the year which incorporates horse racing, archery and wrestling. Unfortunately, we just missed the race in town, but the next day as we drove home, we were lucky enough to see a race outside of Dariv. The races last from 15 to 30 km and are ridden by children 6 to 12 years old, often bareback. Unfortunately, when we got back on the main road and pressed on, we couldn’t reconnect with the Russian van. Lacking cell signal or any way to communicate, we searched with binoculars from a hill and waited for an hour for a passing car to say if they’d seen the Russian van. Both this year and last, I’ve had the sense that navigating on the open steppe must be akin to life on the high seas. I’ve never really been too far out to sea, but with the rolling hills in all directions, the lack of easy features to navigate with, and the isolation, it feels close.

On our last day in Dzereg, we drove into town to see their Nadaam, the most important festival of the year which incorporates horse racing, archery and wrestling. Unfortunately, we just missed the race in town, but the next day as we drove home, we were lucky enough to see a race outside of Dariv. The races last from 15 to 30 km and are ridden by children 6 to 12 years old, often bareback. Unfortunately, when we got back on the main road and pressed on, we couldn’t reconnect with the Russian van. Lacking cell signal or any way to communicate, we searched with binoculars from a hill and waited for an hour for a passing car to say if they’d seen the Russian van. Both this year and last, I’ve had the sense that navigating on the open steppe must be akin to life on the high seas. I’ve never really been too far out to sea, but with the rolling hills in all directions, the lack of easy features to navigate with, and the isolation, it feels close. Anyhow, we soon reconnected and moved slowly east. After two more days, we started coming into Bayanhongor. A few hours outside of town, we stopped by the ger of Nyamsakhin’s brother and were treated to some food and tea. His nephew had a toy gun, and I opened up a play guerilla war wherein we were shot dozens of times. So much for his innocent look and peace sign...

Anyhow, we soon reconnected and moved slowly east. After two more days, we started coming into Bayanhongor. A few hours outside of town, we stopped by the ger of Nyamsakhin’s brother and were treated to some food and tea. His nephew had a toy gun, and I opened up a play guerilla war wherein we were shot dozens of times. So much for his innocent look and peace sign... In Byanhongor, we had a nice dinner and celebrated Naraa’s birthday and said goodbye to Nyamsakhin. The last two days we piled into the Russian van as earlier and pressed on. Back in UB, we cleaned up, feasted and packed our samples for the complicated process of getting them shipped back to the US.

In Byanhongor, we had a nice dinner and celebrated Naraa’s birthday and said goodbye to Nyamsakhin. The last two days we piled into the Russian van as earlier and pressed on. Back in UB, we cleaned up, feasted and packed our samples for the complicated process of getting them shipped back to the US. We were able to hang out a bit more with Ogii and we had a nice dinner with the drivers as well. We even had dinner with Ganaa, our student translator from last year, who just came back from a field mapping course. We also squeezed in some souvenir hunting and I revisited the beautiful Gandantegchinlen Monastery. The largest Buddhist monastery in the country, it is also one of the lucky to survive the communist purges.

We were able to hang out a bit more with Ogii and we had a nice dinner with the drivers as well. We even had dinner with Ganaa, our student translator from last year, who just came back from a field mapping course. We also squeezed in some souvenir hunting and I revisited the beautiful Gandantegchinlen Monastery. The largest Buddhist monastery in the country, it is also one of the lucky to survive the communist purges. Mongolia by the numbersHours driven: Approximately 120Hours driven on pavement: 5?Samples collected: Approximately 400 rock and 50 water samplesAmount of time these samples span: 75 million yearsHot showers: OneLiters of fermented camels’ milk consumed by the group: FiveBooks read: Five...The Value of Nothing by Raj Patel, about the shortcomings of the free market and how to restructure democracy. Mixed Emotions by Greg Child. Writings of one of the most prolific mountaineers of the modern era. Early Days in the Range of Light by Dan Arnold, a former Stanford Alpine Club member. A collection of writings on the pioneering alpinists of the Sierra Nevada from John Muir to Norman Clyde. The World As It Is by Chris Hedges. Quickly becoming one of my favorite authors, Hedges reports on the Middle East, American politics and the decay of the American empire. Kiss or Kill by Mark Twight. Writings of one of the most radical climbers of the modern era. His tales of Khan Tengri and the peaks I’m heading to this summer are particularly thrilling.New favorite albums: One...Mumford and Sons' Sigh No More has been the soundtrack to the trip so far

Mongolia by the numbersHours driven: Approximately 120Hours driven on pavement: 5?Samples collected: Approximately 400 rock and 50 water samplesAmount of time these samples span: 75 million yearsHot showers: OneLiters of fermented camels’ milk consumed by the group: FiveBooks read: Five...The Value of Nothing by Raj Patel, about the shortcomings of the free market and how to restructure democracy. Mixed Emotions by Greg Child. Writings of one of the most prolific mountaineers of the modern era. Early Days in the Range of Light by Dan Arnold, a former Stanford Alpine Club member. A collection of writings on the pioneering alpinists of the Sierra Nevada from John Muir to Norman Clyde. The World As It Is by Chris Hedges. Quickly becoming one of my favorite authors, Hedges reports on the Middle East, American politics and the decay of the American empire. Kiss or Kill by Mark Twight. Writings of one of the most radical climbers of the modern era. His tales of Khan Tengri and the peaks I’m heading to this summer are particularly thrilling.New favorite albums: One...Mumford and Sons' Sigh No More has been the soundtrack to the trip so far

Mongolia Part 1: The Gobi

What a trip it’s been! Ulaanbaatar has all the charm you’d expect of a rapidly developing, ex-communist city. Things are slow, fast and chaotic all at the same time. We knew from last year that we wanted out as fast as possible so as to avoid falling into an uncovered manhole in a jetlagged stupor. After a day of running errands and adjusting to a new pace of life in Ulaanbaatar, we left early for the Gobi. Our group consisted of myself, Jeremy, Derek and Jobe from the US, and Ogii, a Mongolian geology student and translator, Dagi, our cook, and two drivers Naraa and Tsele.

What a trip it’s been! Ulaanbaatar has all the charm you’d expect of a rapidly developing, ex-communist city. Things are slow, fast and chaotic all at the same time. We knew from last year that we wanted out as fast as possible so as to avoid falling into an uncovered manhole in a jetlagged stupor. After a day of running errands and adjusting to a new pace of life in Ulaanbaatar, we left early for the Gobi. Our group consisted of myself, Jeremy, Derek and Jobe from the US, and Ogii, a Mongolian geology student and translator, Dagi, our cook, and two drivers Naraa and Tsele.

We ditched the pavement after hardly an hour on the potholed pavement. Each day we rotated seating arrangements, and I took the first day in the trusty, if not always somewhat broken, Russian van. Just like getting sea legs, it takes a while to get used to life on the dusty steppe, and the learning curve for riding in the Ruski is steep. We all came away with a few interesting bruises. The next day, we reached Bayn Zag in the afternoon heat, and worked the main part of the Flaming Cliffs, a touristy dinosaur fossil locality.

After Bayn Zag, we settled into a rhythm as a group. We would drive around half a day to our next locality, scout it out if not sample it in the afternoon, then finish work or move on in the morning. We kept the momentum up through all of our Gobi localities, knowing that we still had a long road ahead to western Mongolia. We only took one day off late in the trip to deal with a car problem, and only once did we stay in the same camp two nights in a row.

The Gobi is a beautiful but fairly challenging place. It wasn’t crippling heat but rather constant wind and sand that made our bones weary. We’d wake up to a fresh coat of sand inside our tents each morning, meals would be prepared and eaten behind vehicles or rocks for cover. Still, nothing was spared from the sand. The days on the road were challenging as well. We frequently encountered impassable sections. Navigating by GPS and going days on end without seeing anyone, we had to make sound decisions. Tsele, our Land Cruiser driver, was a nice man, but didn’t know much about his vehicle. We chuckled when he always engaged the rear defrost instead of 4WD when we got in a jam. Sometimes, we were lucky to cover 5km in an hour…at most it was 20 or 30. But the places were as wild as it gets.

The Gobi is a beautiful but fairly challenging place. It wasn’t crippling heat but rather constant wind and sand that made our bones weary. We’d wake up to a fresh coat of sand inside our tents each morning, meals would be prepared and eaten behind vehicles or rocks for cover. Still, nothing was spared from the sand. The days on the road were challenging as well. We frequently encountered impassable sections. Navigating by GPS and going days on end without seeing anyone, we had to make sound decisions. Tsele, our Land Cruiser driver, was a nice man, but didn’t know much about his vehicle. We chuckled when he always engaged the rear defrost instead of 4WD when we got in a jam. Sometimes, we were lucky to cover 5km in an hour…at most it was 20 or 30. But the places were as wild as it gets. After Bayn Zag, we headed west toward Nemegt. Partway through the second day, we crossed the largest sand dunes in Mongolia. The scenery looked straight out of a movie. We did the classic dune running and jumping. Being an idiot, as usual, I think I broke my tailbone on one of them. “Oh great, I thought, bumpy driving will be the missing ingredient to make this a really fun trip.” The rest of the trip, the tailbone was always with me, but I’ve found a few sitting strategies so I’m not in constant pain. Once we crossed the dunes, we were in a different dimension. Now, not a single tourist had reason to be where we were, and I got the sense that many locals didn’t even know why we’d keep pushing west.

After Bayn Zag, we headed west toward Nemegt. Partway through the second day, we crossed the largest sand dunes in Mongolia. The scenery looked straight out of a movie. We did the classic dune running and jumping. Being an idiot, as usual, I think I broke my tailbone on one of them. “Oh great, I thought, bumpy driving will be the missing ingredient to make this a really fun trip.” The rest of the trip, the tailbone was always with me, but I’ve found a few sitting strategies so I’m not in constant pain. Once we crossed the dunes, we were in a different dimension. Now, not a single tourist had reason to be where we were, and I got the sense that many locals didn’t even know why we’d keep pushing west.

Jeremy and I looked at each other knowingly. I think he said it first, “Is this as far out as you’ve ever been?” I immediately said yes, and said I was thinking of asking him the same. He said only the remote northern slopes of Alaska came close. Nemegt was unbelievably beautiful. The badlands looked like the great parks of Utah, except we had it to ourselves. The layout was amazing, and we scrambled up spires and ridges only to find miles more beyond us. I went for an amazing run along those knife edge ridges and then dropped down into a dry wash back to camp. Birds would come along and play. I always took note of the buzzards and eagles, thinking they may look to us as their next meal.

Jeremy and I looked at each other knowingly. I think he said it first, “Is this as far out as you’ve ever been?” I immediately said yes, and said I was thinking of asking him the same. He said only the remote northern slopes of Alaska came close. Nemegt was unbelievably beautiful. The badlands looked like the great parks of Utah, except we had it to ourselves. The layout was amazing, and we scrambled up spires and ridges only to find miles more beyond us. I went for an amazing run along those knife edge ridges and then dropped down into a dry wash back to camp. Birds would come along and play. I always took note of the buzzards and eagles, thinking they may look to us as their next meal.

The second day at Nemegt, Jobe and I headed off to complete our sampling of the white unit at the top of the main sections, while Derek, Jeremy and Ogii headed east to look at some new sections. As we were finishing the bottom of our peaklet above a gravelly plateau, I remarked to Jobe, “Hey, this could actually be something.” Closer inspection revealed that I was in fact, looking at a dinosaur. Then, once we adjusted our eyes, bones started appearing everywhere. It was hard to even walk without stepping on them. A few meters to the left, I found a large bone, then down in a wash, two more including a huge vertebrae. I’m not much of a fossil hunter, but I do approach science as a simple observationalist. Moments like these definitely make things pop into focus...”Oh, hey, it really does make sense, and you can go out there and see it.”

Stay tuned for Part 2 in a few days. I leave for the mountains on July 8th, and will reach Lenin Peak base camp after about 60 hours of travel. For the time being, I’m showering, sorting samples with Jeremy, and stuffing my face full of Indian food, “Mexican” food, and khuurshuur, Mongolian fried dumplings to fatten up for the mountain. I've been running hard and I'm ready to go, tailbone be damned.

Altay

Hey everyone,This is the first town of any size that we've encountered. Everyone's in good spirits after quite a lot of bumpy and dusty travel. Our original Land Cruiser (and driver Tsele) had to be towed all the way back to Ulaanbaatar. As far as we can guess, the fuel filter/fuel injection was totally shot, as well as maybe the transmission. Our drivers attempted to fix this by breaking a hole in the exhaust with a rock hammer?!? and our fears were confirmed when we reached town. Anyhow, we all huddled into the Russian van for quite the ride across some of the craziest roads yet to Biger. There, we met a wonderful new Land Cruiser and driver Nyamsaikhan who scrambled out from Bayanhongor to meet us. By all accounts, he's a pretty rugged guy, and a really nice addition to the crew. Our work in Biger went unbelievably well, and we haven't missed a beat. We're now poised to take our first day, or half-day off tomorrow, before driving west to Darvi and Dzereg. We'll turn back towards Ulaanbaatar no later than July 1st, budgeting around 4 days for the drive across the country.I'm feeling really well, and have been able to go on some amazing runs out here. We're actually at a bit of altitude (a few nights ago we slept around 8000 ft), so maybe some of my fitness and acclimatization will help for the upcoming climbs. I've also gotten quite a bit of reading done and have enjoyed passing the evenings laughing and joking with the Mongolians. Derek, Jeremy and Jobe are hilarious as usual.Take care,Hari

Ulaanbaatar

Greetings from the capital of Mongolia! With over 60% nomads, UB (pop. 1 million) is really Mongolia's only city, with other towns all under 40,000. UB is an interesting, rapidly growing city, with a very eclectic patchwork of old and new. It looks like we're all set for an early departure to the Gobi Desert tomorrow. We spent the day changing money, picking up some last minute field supplies and sorting out field equipment. Things here feel pretty similar to last year, but there's certainly a lot of hustle and bustle into the leadup to the Parliamentary elections on the 28th. With recent issues including the former president being arrested on corruption charges, and a lot of seats up for grabs, there's a lot of anticipation.

It looks like we're all set for an early departure to the Gobi Desert tomorrow. We spent the day changing money, picking up some last minute field supplies and sorting out field equipment. Things here feel pretty similar to last year, but there's certainly a lot of hustle and bustle into the leadup to the Parliamentary elections on the 28th. With recent issues including the former president being arrested on corruption charges, and a lot of seats up for grabs, there's a lot of anticipation. Anyhow, our rough plan is as follows:We'll head to the Bayn Dzag, near the town of Dalanzadgad. Bayn Dzag is famous for some of the best dinosaur fossil localities in the world. There, we'll sample paleosols, ancient soils, for clay and carbonate minerals which can tell us about the climatic conditions when they were deposited. After Bayn Dzag, we travel west into the remote Nemegt Basin, where we'll continue sampling. After Nemegt, we have planned a very adventurous several hundred mile drive to the northwest to more field sites near Altay. Finally, we travel west to the town of Khovd along a main road (main roads are still pretty wild though!) and sample at 3 or so other sites. From Khovd, we'll begin the several day drive back across the country to UB, completing our several thousand mile clockwise loop. We plan on being out in the field for about three weeks as we're scheduled to leave the country on June 8. I'll check in with brief updates from the field or the occasional town along the way.Take care,Hari

Anyhow, our rough plan is as follows:We'll head to the Bayn Dzag, near the town of Dalanzadgad. Bayn Dzag is famous for some of the best dinosaur fossil localities in the world. There, we'll sample paleosols, ancient soils, for clay and carbonate minerals which can tell us about the climatic conditions when they were deposited. After Bayn Dzag, we travel west into the remote Nemegt Basin, where we'll continue sampling. After Nemegt, we have planned a very adventurous several hundred mile drive to the northwest to more field sites near Altay. Finally, we travel west to the town of Khovd along a main road (main roads are still pretty wild though!) and sample at 3 or so other sites. From Khovd, we'll begin the several day drive back across the country to UB, completing our several thousand mile clockwise loop. We plan on being out in the field for about three weeks as we're scheduled to leave the country on June 8. I'll check in with brief updates from the field or the occasional town along the way.Take care,Hari