Mélange

Unnamed lake, Eastern Sierra, CA

View from the summit of Alta Peak, western Sierra Nevada

General Sherman, the world's largest tree

Shasta winter summit bivouac

A late spring trip to the Eastern Sierra:

Red Slate Mtn

Banner Peak, my objective for the day

A road trip to Oregon and climb of Mt Hood:

Walter likes camping

Michelle's car camping spread!

Walter meets a marmot!

A 40-mile, 13,500 ft elevation gain dayclimb of remote Mt. Kaweah:

Rodent-proofing in Mineral King

Gorgeous Spring Lake

Big Five Lakes

LeConte, Corcoran and Langley

Russell and Whitney

Last view of the Kaweahs

Solstice

Once again, I found myself checking the White Mountains weather forecasts. They looked mediocre...a bit of wind near the summit but probably not too much. About two days before a storm. And once again, I decided to head up into the unknown, the only difference being that this month's attempt on Boundary Peak, the highest point in Nevada and the proposed end point of my Thanksgiving traverse, would be a simple dayclimb with an easy retreat should things deteriorate.

The climb was enjoyable. Cold and gray, but unbelievably quiet and peaceful. Solitude on the solstice.

Again, two bighorn sheep greeted me near the White Mountain crest. They paused, acknowledged me, then gracefully traversed over the ridge into California.

The wind picked up quite a lot near the summit, so it was not the day for a summit lunch break. But I did have the opportunity to look all the way southward across the White Mountain traverse to see the landscape where I was caught, overpowered, and humbled a few weeks ago. It was an emotional experience to interact with this landscape once again.

Loose ends

I've come out of the Thanksgiving experience. The psychological trauma has passed. New memories and details have emerged. For example, I remember during my downclimb from the ridge being so dehydrated that my vision was quite blurry. And while climbing just 100 feet above the creek, I pressed my lips to a moist streak on the rock wall to see if I could get some moisture. I remember thinking that I wasn't sure if I'd be able to complete the downclimb or have the strength to reascend back to the ridge. I found this lower section on Google Earth:

A few more details to share...

Paul, my driver, revisited the area to take photos of the scene during good daylight.

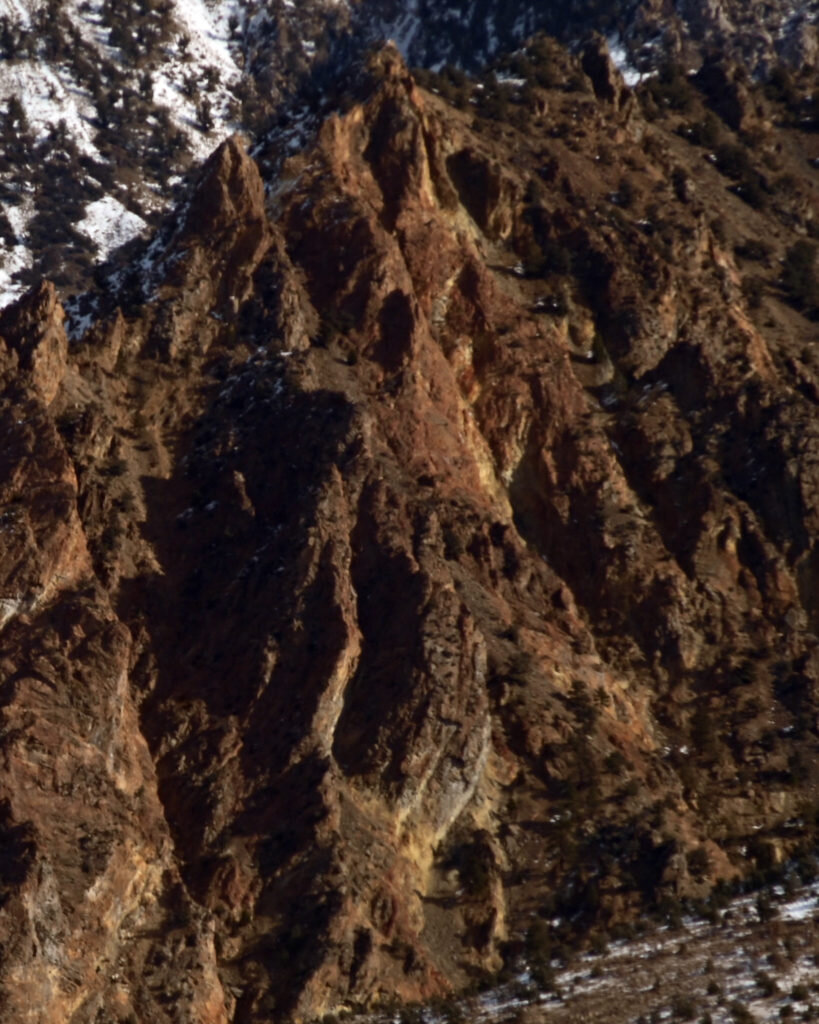

Mono County Search and Rescue posted their mission report from the incident. It was eye opening. I knew they had a rough time, but I didn't know a rescuer had been injured (by rockfall) looking for me. I'm quite saddened, but not surprised...in many ways it was a blessing being alone on such dangerous and unstable terrain. One photo tells more of the story than I ever could:

My whole life I've been searching for mastery. I've always found it most interesting and most rewarding to dig deeply into my passions, from yoyos and other skill toys, to earth science, running and alpinism. In many of these cases, I reached a high level of proficiency, but often felt like I left a few rungs on the ladder.

The White Mountains self-rescue was the one moment in my life where I actually realized my full potential. On a physical level, it required more calculated execution than my finest race ever in track. From a mental focus perspective, it was significantly harder than descending the world's 13th highest mountain without, food, water, oxygen or the ability to clearly see this summer. And in terms of problem solving, nothing in my life has ever presented a bigger, more complex set of challenges, including my PhD qualifying exams. For thirty hours, I was perfect. But it doesn't feel an accomplishment, just a singular moment of intensity.

I will become even more adventurous in the future. As I build more stability in my professional, financial and personal life, it will become increasingly important to add risk rather than retreat into security. Mountains are just a canvas for my fullest expression.

Thankful to be here

"No matter how powerful the illusion, you are never in charge"

Me

This is how it begins

1. You’re outside over a day away from another human. Ok,technically, you’re over 13,000 ft on the longest, most remote and highestcontinuous ridgeline in the lower 48…the White Mountains of CA/NV. You’re overtwice the height of the Grand Canyon above safety. But the mountain superlativesare almost irrelevant because…

2. You’re hit with an unforecasted extreme wind event with confirmed gusts over 100 mph. That’s equivalent to at least a category 2 but likely category 3 hurricane. Except…

3. Air temperature is about five degrees Farenheit. Much more detail of the storm and the damage it caused in the valleys will be discussed below. But for now…

Got any ideas? Great! Let me rule them all out for you:

Pitch a tent/bundle up/hunker down. All of these are not even worth considering. The wind was lifting me airborne and blowing me over (160lbs + 40lb pack). Pitching a tent would be extremely challenging in winds 1/3 this powerful. Even if a tent were already pitched it would be immediately shredded. So, no, you cannot make a shelter, no you cannot light a stove (to melt snow for water) and no you can’t even bundle up with those extra jackets in your pack. If you take your pack off and let go of it for any reason, you will likely watch it get blown into Nevada. It is too windy to access anything in your pack. And of course, wind chill is off the charts. If you stop moving for any reason you’re not gonna make it. Oh, and by the way, a storm is coming tomorrow at nightfall and is expected to drop five feet of snow. If you don’t have a plan to get completely back to civilization in the next 36 hours that’s it.

Get rescued. How? No human could reach you, and a helicopter…are you kidding? Heli rescues are not possible in winds even half this powerful.

Find the best way down. Great idea! There are noroutes off the ridge from where you are. It is too windy to read a map. Thewind creates a ground blizzard effect where windblown snow and ice make it notworth its while. I made several attempts to evaluate multiple routes down butwas unable to do so. There are 4 directions to travel:

Forward:This would be the best option over 95% of the time. But it’s over 21 miles ofridgeline to the car. Unless the wind dies down, you probably won’t make it morethan another couple hours on the ridge.

Backward/reversethe route: There is a technical, exposed section of ridgeline that preventsthis. This was extremely delicate rock climbing the day before and you’dunquestionably get blown off. Also, even if this were possible, this is for theprivilege of having to re-ascend the third highest peak in California, White MountainPeak, likely with significantly higher winds.

Bail east into Nevada: One look down this way and you realize it’s a horror show. Geologically, the Whites are bounded by a normal fault on the West, meaning that the east side is the “dip slope” which is less steep but muuuch longer. Plus, then you’re descending into Fish Lake Valley (coincidentally where I did much of my PhD work). It’s extremely remote, without infrastructure or resources outside of the tiny outpost of Dyer, NV.

Bail west into California: First of all, its hard to even glance into the wind. So it’s hard to tell, but you’re next to the start of a ridge that is very easy at the top but it’s quite obvious that it would be a horror show. No one in their right mind would do this. On the upside, there are lots of resources, communications, search and rescue in CA.

Your move.

The vision

Traversing the White Mountains is one of the most unique adventures one can find. Their remoteness, the starkness of the tundra landscape and the beauty of the Sierra and other adjacent ranges make this trip an experience to remember. Add the ancient Bristlecone Pines, the oldest living things on Earth at over 4000 years, and you truly gain an appreciation for our relationship with the natural world. But you'll have to earn it. Traverses are done only by several parties each summer, and teams often take up to five days. The trip is seldom done in the other seasons. I'm only aware of two wintertime traverses, the first being done by Eastern Sierra legends Jay Jensen, George Miller, Galen Rowell and Dave Sharp on a National Geographic sponsored expedition in February 1974. Unlike my trip, this adventure was in the heart of winter and traversed the entire range and done on skis. The team took 16 days and encountered serious storms, including one with 100+ mph winds that trapped them for five days. Ironically, National Geographic decided not to run the article because of "lack of life-threatening circumstances!"

"For me, seeing the stark beauty and remoteness of the range in winter, with constant views of the snowy Sierra as if from an aircraft, rivals any mountain experience I've had in the greater ranges of the world"

Galen Rowell

I've dreamt of the White Mountains traverse for about a decade and only this fall did I start to think it could work. Not only did I need the requisite fitness, logistical planning and motivation, but I needed to get lucky with the conditions. For one, there needed to be just enough snow to melt for water (as there's no water on the ridge) but not so much that it slows travel. I needed to be able to hike efficiently or it wasn't supposed to work. This is why the best time for the traverse is probably at the very end of the spring when there are just a few remaining snowdrifts as a water source but otherwise summer conditions.

Over the last few months, I'd been meticulously planning the trip. All of the logistics, mapping the route in great detail, finding all available trip reports and mining them for any usable data, downloading and analyzing historical weather data, checking webcams and checking about five different weather reports daily in the weeks leading up to the trip.

This fall set up well for weather. It was a peculiarly warm and dry fall. At first, I was excited, but then almost a little worried that not a single storm would blanket the range. But just before my window over Thanksgiving break, a small storm dropped the exact right amount of snow! Not only that, but the weather reports improved for my proposed dates. Now, a window of decent weather preceded a well-defined storm that would mark the true start of winter. This was it...the only window since spring that the White Mountain Traverse would be ready.

Backcountry bliss

After class on Friday, I drove out to Reno. The next morning, I drove to Queen Mine road on the north side of the range just north of Boundary Peak (13,147 ft), the highest point in Nevada. There, I met Paul Fretheim, owner of East Side Sierra Shuttle, who helped my car shuttle between the my car which we left at 9,200 ft and my trailhead at the base of White Mountain Peak (14,252 ft), the third highest peak in California.

I got started in early afternoon on Saturday the 23rd, and after a few hours of easy warm hiking, I reached Black Eagle Camp. These beautiful, free and well-maintained cabins are located at the old Champion Sparkplug mine, a mine operational in the 1920s-1940s for andalusite, used to make the heat-resistant ceramics in sparkplugs. It's a really splendid place, with all kinds of cool stuff from the mining days, a museum and of course the cabins.

The next morning, I got a pre-dawn start and caught the morning alpenglow on the entire High Sierra. It was a sight to behold. While most of the east ridge, one of the longest routes in the nation at 9,500 ft of vertical, is poor climbing, the setting makes it a truly special place. Part way up, I had an incredibly close, long and intimate encounter with a baby bighorn sheep and then her mother. It was a spiritual moment as we all acknowledged each other. Not only that but their tracks showed me the way up the ridge. And later in the trip, it was perhaps the bighorn tracks that helped me stay alive.

After about nine hours of climbing, I found myself alone on the summit.

As it was late afternoon, I made an effort to press on and get as much of the traverse done as possible. At the very least, I wanted to cross the first technical section in the daylight so I could find a nice place to camp. The weather was blustery, but what else would you expect on such a high summit?

I ended up not quite making it across the tricky section by nightfall, requiring that I downclimb the crux moves by headlamp. The photos below, courtesy of Summitpost.org user Daria show this section. So add in that this was at night and partially covered in snow. While well within my abilities during good conditions, it was this section of delicate rock climbing that prevented my retreat during the wind event.

The storm

Things started to pick up just as I was looking for a tent site. I finally settled on chopping a nice little platform adjacent to a col because it was somewhat protected behind some rocks. As it was a bit windy, I focused quite hard on doing everything right in my tent setup so as not to lose my tent or a pole. After guying out the tent quite well, I settled inside, melted enough snow for a liter and a half of water, had a nice dinner and settled in for the evening. A few hours into the night, things began to worsen. The tent was now hitting me in the face. What a nuisance I thought! But by the time my alarm went off for the morning, half the tent was compressed by a newly-formed snow drift. I knew I needed to keep moving to get off the ridge before the snowstorm, so even though conventional wisdom would be to hang tight in the tent, I knew I at least needed to make some progress. I packed up and quickly got moving.

Initially, I thought, wow, this is really bad weather. What I didn't realize, is that unbeknownst to me, the storm was rapidly intensifying, leading the National Weather Service to issue a wind advisory, specifically citing my region as the worst of it:

What ensued was a truly legendary storm, ultimately becoming a "bomb cyclone" (one that rapidly intensifies). The storm set all time records for low pressure of a US West Coast storm, and I had direct line-of-sight across the Pacific to Asia.

Some facts about the wind event relayed to me afterwards by the Mono County Sheriff and Search and Rescue Coordinator:

Near Mono Lake, power poles were downed. Not the lines, the wooden poles snapped. I was approximately 7,000 ft higher in elevation on a ridge.

At Mammoth Lakes Airport, a gust of 94 mph was recorded. Rocks were picked up by the wind, destroying all of the cars parked there.

The strongest wind gust recorded was at Crowley Lake, 7,000 ft below and 25 miles due west of me:

Highway 6, 10,000 ft below me was closed due to wind.

Back up on the mountain, the winds dramatically intensified when I was required to traverse saddles and flats. In addition, I believe the storm intensified. I started to get spun around when the wind caught my pack. I would lean 45 degrees into the wind, plant both trekking poles and do as hard of a lateral lunge as I could, then get blown airborne and tossed onto the tundra. At one point, I hid behind a small rock and attempted to glance at my map but was unable. It was a ground blizzard, where airborne snow and ice not only pelted exposed skin but also reduced visibility. About two hours after leaving my tent, I was in the scenario outlined at the beginning. So, what did I do? I bailed down the ridge into California. I could barely see due to the wind, but from what I could gather, it was absolutely sickening. Something I would never choose to do in a million years.

But I was past choices. From this moment on, I was on the ride.

As it was directly into the wind, I resorted to huddling during the gusts, then running full strength as low as I could before hitting the ground. Like the football sled push drill. Rinse repeat.

After losing a bit of elevation and climbing behind , things did in fact calm down. The upper ridge was quite straightforward, and even when things became a scramble it was still a joy to be a bit more out of the wind. At 11,000 ft I tried to light my stove to melt snow but it was still too windy. I pressed on down increasingly technical rock to a bit over 9,000 ft. There, I traversed on the north side (steep, snow-covered rock) to bypass four towers. As I approached the final saddle after which it would been a straightforward walk through sagebrush to the valley floor, I stopped in my tracks. Aloud, I said, "If that's my ridge, I need SAR."

I took the photos below on my phone for the sole purpose of aiding search and rescue.

At around 3:30PM and from this viewpoint, I first called Paul, then the White Mountain Ranger District in Bishop (I think the ranger there may have thought I was the somewhat typical exhausted/offroute hiker: "Well, there's no way a helicopter going to get you in this wind.") I responded, "Oh, I'm aware of that! I just need to get a line of communication going so someone can help me with a plan." I was transferred to Inyo County Sheriff and InyoSAR coordinator Victor Lawson. While first determining that I wasn't in Inyo County, and therefore he wouldn't be able to help me (DAMMMIT!) he did stay on the line, pull up my coordinates and start to analyze slopes on CalTopo. He texted me a SARtopo file plotted with a proposed route. Unfortunately, I actually had higher resolution data on my phone, not to mention super high-definition "actual vision" showing that the descent looked like hell at best. He coordinated with Mono County Sheriff and MonoSAR coordinator John Pelichowski. He gave the thumbs up to Victor and my plan, and we coordinated some other details. It was clear that this was really bad and the clock was ticking. We agreed that I would go for it, aiming for a chute they'd identified about 200-300 feet east of me. At first light, a SAR team would start up to search.

The dark art of getting down

First, I traversed back around the tower, putting the microspikes back on for the sketchy snow. After a time, I reached the saddle between the correct spires and started down the recommended chute. It was an extremely loose, tricky, then sketchy, then scary downclimb. I stopped when the rocks I was slipping on shot over the lip of a 150 foot dry waterfall. To avoid the loose rock, I chose to rock climb the buttress to the right of the chute, which went well into the 5th-class (roped rock climbing). All of the rock, from this point on, was terrible. The worst I've encountered. The largest blocks my feet dislodged were the size of a dinner table. Handholds broke.

I climbed as high as I needed to until I could traverse until the next chute west. An extremely technical rock traverse brought me into the second chute. As with the first chute, it was a horror show. It seemed everything on the face would just get steeper, ending in cliffs. These bands were too small to pick up on the satellite imagery and topo maps, but still far too big to deal with in real life: 30-150 feet. I reascended on another buttress, aiming to explore the next chute but the rock was even more technical. The chutes to my right were near vertical and the buttress was too technical to climb, so I jumped back in the loose chute to slide my way the few hundred feet uphill back to the ridge.

There, Sheriff Pelichowski and I texted. I tried to call Michelle, but almost immediately was called by her parents with confusing questions about Michelle's whereabouts. Her car was stranded in Nevada and the police were worried and looking for her! I then was called by a Santa Clara County Sheriff asking all sorts of rigamaroll about her wellbeing. Once he was sufficiently convinced that she was ok and that I had in fact parked the car in Nevada, he was like, "How are you, by the way?" It's like, dude the only reason I picked up is because I thought this was search and rescue. "Well, I'll let you get back to it then."

I did get through to Michelle as it got pitch black. I strapped on the microspikes, made another long, sketchy snow traverse back up the ridge past two towers to the largest chute. At least this one went the furthest down. Most of it wasn't that bad. I mean, normally I'd consider it horrible. But in this case, I was just thrilled to be moving downward without having to be concerned about dying each move. I made it most of the way down, traversed skiers right across a crappy buttress and dropped into the chute that I believed set me up with the best chance for success. At last, I could hear and see the stream. But I was beyond dismayed that everything in the gorge dropped into a narrow, near-vertical slot canyon. Just 150 feet above the creek, I stood at the lip of a dry waterfall.

By this point, I'd been downclimbing, reascending, and traversing for a few hours in the pitch black. I'd been cautious to eat hardly anything because I needed to focus on hydration. Over 12.5 hours, I consumed a quarter liter of water. The sound of rushing water was torture.

But at least the drainage I was in had a tiny bit of snow in it. I chose to do as I'd done before. I worked my way downstream and systematically work every single option. It's crazy to say this, but it was significantly worse than everything before. The rock was much steeper, and the traversing was outrageously hard. Fear had left me far earlier.

I worked about eight different options, each with their own challenges. One unbelievably hard rock climb up and left was about 250 feet above the black. I ascended extremely technical, poor quality rock, perhaps in the 5.6-5.7 range. Following this final buttress, I saw an easier slope in all directions but unfortunately no descent through the final 30 or so feet to the creek. In an unbelievable moment, I saw a vehicle driving up toward me in the valley! It was Paul. We communicated and ended up telling him to go home as I knew there was no way I'd get out that day.

I communicated again with Sheriff Pelichowski and I told him that I'd head back upstream to the snow and bivy for the night. I ascended high to avoid all of the cliffs and soon reached the landmark dry waterfall. I descended, eager to reach the snow patch only to find that it was just calcite deposits on the rock! From a distance and under headlamp light, I had been tricked. What an unbelievable blow. This was perhaps the lowest moment of the ordeal.

Re-ascend a few thousand feet to actual snow? There, I'd be able to hydrate and communicate. On the other hand, I'd be moving a significant distance in the wrong direction. And by this point, I was more focused on the fact that I had less than 24 hours to get out or I'd be dead. Snow was forecasted to start late afternoon or evening both trapping me and halting rescue efforts.

I made one more hail mary attempt to descend before reascending to the snow. I chose to start with...the waterfall. In a strange sort of luck, the slippery, water-polished stone actually became stickier on the streaky deposits. It felt great. I quickly descended most of the way down the cliff before the final escarpment. Here, I traversed upstream on steeper but better rock. It was clear that this was the only option that would go, as the gorge came to its most impressively vertical at this moment.

It worked. I made it work. It was outrageous, but with the slightly stronger, stickier rock, I was able to make some more gymnastic moves that would have been suicidal on the bad stuff. But make no mistake, it was extreme. It was technical. It was so messed up.

And just like that, I was at the creek on flat-ish ground. I dropped my pack, grabbed my bottle, dunked it in the stream and chugged until brain freeze. And again.

The last day

I quickly found a terrible, but workable platform to pitch my tent. Despite having jagged, microwave-sized blocks, I hastily excavated the boulders, filled in with smaller rocks and pitched my tent. My sleeping pad immediately popped due to the sharp rocks underneath, so I slept on my pack, down jacket and heavy gloves to insulate from the cold. But I was able to eat some great food, down a liter of water and get to bed by 11. After all, SAR was coming up at first light and I wanted to be moving down before dawn to give ourselves the best chance of getting through the canyon.

POP POP BOOM POP!

I instantly threw my arms over my head and braced for impact. An enormous rockfall funneled down the chute and launched over the lip of the waterfall pitch just 50 feet away, exploding on impact and sending debris toward my tent. At this point, I was resigned to the fact that I was trapped in the slot at the base of the 1,700 ft face made up of the loosest rock ready to slide. Still unable to control the situation, I fell back asleep.

I woke up, broke camp, and started down by headlamp an hour before daybreak. The canyon was immediately bushwhacking hell. The worst I've ever experienced even compared to the most choked out Sierran drainages. But it didn't matter. I belly crawled over long thickets of briars, systematically broke willow branches, and every twenty feet, forged a way through the brush to cross the creek on iced-over boulders. But it was okay...I was moving.

The first time my heart sank was when the canyon narrowed to a single slot where the stream plunged over a 100 ft waterfall. Little did I know that half a dozen waterfalls lay below. Unable to do anything but improvise, I repeatedly free soloed up the walls, traversed over awful, loose terrain, and then soloed down to the drainages. Sometimes, it took 40 minutes of sustained rock climbing to cover just 10 feet.

I tracked my forward progress on my phone counting down the feet until the mouth of the canyon. Just 700 feet from safety, I came across a final cliff band. Once again, a couple bighorn sheep tracks led to the base of the right hand cliff, where a 6 inch wide ledge ascended up and around a corner. I delicately climbed the smooth, downward sloping ledge for about 30 feet until I reached a bench, which I traversed along a bighorn trail crossing several loose chutes. At last, I found a tricky but possible talus slope back down to the final cliff. I traversed alluvium beneath the canyon floor, holding on to a tiny bush which broke. But I pulled the final move and reached the floor. After that, a tiny bit of bushwhacking, then wading through 3 foot deep leaves led me to a broad dry wash. Here, I jubilantly messaged SAR to retreat and rendezvous at the cars. I heard the team shout "Hello!" I yelled back, but got no response so I continued down. Once again, I heard "HELLOO!" I spun around and gazed upwards to three figures waving from a small summit above. I screamed and waved back, then waited as I watched them descend. It had taken six hours to cover the final mile. But it was over.

Perspective

Giving Thanks

It's hard to describe the gratitude I have to be here this Thanksgiving. In particular, I am thankful to:

Michelle and my family

Inyo County Sheriff Victor Lawson, Inyo SAR

Mono County Sheriff John Pelichowski

Mono County Search and Rescue. Donate here.

Paul Fretheim, East Side Sierra Shuttle

Max Ferrero and Mint Condition Fitness

Full Value in the High Sierra

I returned from some much-appreciated play time on the Eastside. I'm slowly working my way through the Sierra Peak Section's Emblem Peaks: 15 of the Sierra's most prominent peaks as a way of exploring new parts of the range. First up was Matterhorn Peak which was in pretty good shape despite a bit of awkward postholing on the approach.

I returned from some much-appreciated play time on the Eastside. I'm slowly working my way through the Sierra Peak Section's Emblem Peaks: 15 of the Sierra's most prominent peaks as a way of exploring new parts of the range. First up was Matterhorn Peak which was in pretty good shape despite a bit of awkward postholing on the approach.

Then, escaping a violent cold and wind storm, I went to the southernmost Sierra to Olancha Peak, where I had my first ever bighorn sheep encounter despite countless trips to the Williamson region and other remote parts of the Southern Sierra.

Then, escaping a violent cold and wind storm, I went to the southernmost Sierra to Olancha Peak, where I had my first ever bighorn sheep encounter despite countless trips to the Williamson region and other remote parts of the Southern Sierra.

After a trip to Tucson for the holidays and adequate time for my blisters to heal, I returned to Bishop for a day of full-value alpine climbing on Mount Darwin, including a mountain bike to the base, a trip over Lamarck Col and a fantastic climb up perfect styrofoam on the North Face.

After a trip to Tucson for the holidays and adequate time for my blisters to heal, I returned to Bishop for a day of full-value alpine climbing on Mount Darwin, including a mountain bike to the base, a trip over Lamarck Col and a fantastic climb up perfect styrofoam on the North Face.

The casual thirteen hours car-to-car from Aspendell showed me that my fitness is right where I want it to be and my approach to the mountains is as solid as ever. Here's to 2018!

The casual thirteen hours car-to-car from Aspendell showed me that my fitness is right where I want it to be and my approach to the mountains is as solid as ever. Here's to 2018!

Big Will and the California Fourteeners

"Going to the mountains is going home" -John Muir

It's been too long. I joined the machine and got a "Real Job." I built my own lab this past fall (more on that later!). But the High Sierra are my home away from home. Last weekend I completed a seven year journey to climb each California's fifteen peaks over 14,000 ft...and each with a twist, be it a linkup, speed ascent, winter ascent or a non-standard route.

No peak was more challenging nor turned me back more than bulky Mount Williamson. It's not that Williamson is the most technical, nor the most mileage. It's just one of the bigger, more inaccessible piles of rubble you'll encounter. Williamson's routes are nearly Alaskan or Himalayan in proportion as they start from the Owens Valley floor, over 8,000 ft below the summit. They involve miles of up and down trail, thousands of feet of bushwhacking, scree, scrambling or rock climbing. For my fifth (or thereabouts) attempt on Williamson, I opted for the loose, brush-filled, icy boulder-hopping, snow climbing and scrambling sufferfest that is the North Fork of Bairs Creek. I don't know what's wrong with me but I eat this stuff up!

No peak was more challenging nor turned me back more than bulky Mount Williamson. It's not that Williamson is the most technical, nor the most mileage. It's just one of the bigger, more inaccessible piles of rubble you'll encounter. Williamson's routes are nearly Alaskan or Himalayan in proportion as they start from the Owens Valley floor, over 8,000 ft below the summit. They involve miles of up and down trail, thousands of feet of bushwhacking, scree, scrambling or rock climbing. For my fifth (or thereabouts) attempt on Williamson, I opted for the loose, brush-filled, icy boulder-hopping, snow climbing and scrambling sufferfest that is the North Fork of Bairs Creek. I don't know what's wrong with me but I eat this stuff up!

I got a super late start on Saturday because I-5 had been closed the day before due to an accident. I climbed the 1,500 or so feet to the "hard to find" notch, dropped down into the icy creek bed, and ascended thousands of feet of loose rock, willows and thorns to a decent bivy spot at ~9,600 ft. I felt quite good, hydrated well and had a nice dinner of noodle soup before turning in for the night. In the morning, I brewed up, hydrated and boulder hopped thousands of feet up to the crux of the route, a snowy couloir that provided excellent cramponing up to the 13,000 ft plateau beneath the summit slopes. A while later, I was on top, making the first winter ascent of the season and with the high sierra to myself. A fast and relatively uneventful descent (minus some inevitable thrashing) had me eating a nice dinner in town.

I got a super late start on Saturday because I-5 had been closed the day before due to an accident. I climbed the 1,500 or so feet to the "hard to find" notch, dropped down into the icy creek bed, and ascended thousands of feet of loose rock, willows and thorns to a decent bivy spot at ~9,600 ft. I felt quite good, hydrated well and had a nice dinner of noodle soup before turning in for the night. In the morning, I brewed up, hydrated and boulder hopped thousands of feet up to the crux of the route, a snowy couloir that provided excellent cramponing up to the 13,000 ft plateau beneath the summit slopes. A while later, I was on top, making the first winter ascent of the season and with the high sierra to myself. A fast and relatively uneventful descent (minus some inevitable thrashing) had me eating a nice dinner in town.

The Fourtneeners, a retrospectiveThanks to all with whom I shared these magnificent adventures...they wouldn't have been the same without you!! Here are some highlights from fourteener trips...Langley (with Mike) We went up this one dry Thanksgiving via a variation of Old Army Pass. The climbing wasn't the most memorable, but Mike ate a heroic amount of french fries in Lone Pine!

The Fourtneeners, a retrospectiveThanks to all with whom I shared these magnificent adventures...they wouldn't have been the same without you!! Here are some highlights from fourteener trips...Langley (with Mike) We went up this one dry Thanksgiving via a variation of Old Army Pass. The climbing wasn't the most memorable, but Mike ate a heroic amount of french fries in Lone Pine! Russell, Whitney, Muir (and Keeler Needle) (with John and Dave) What a blast. We went up the East Ridge of Russell...perhaps the finest 3rd class route I've ever been on (sorry Keyhole Route on Long's Peak). I threw in Keeler and Muir for good measure and then had a death march back to the Portal.

Russell, Whitney, Muir (and Keeler Needle) (with John and Dave) What a blast. We went up the East Ridge of Russell...perhaps the finest 3rd class route I've ever been on (sorry Keyhole Route on Long's Peak). I threw in Keeler and Muir for good measure and then had a death march back to the Portal.

Williamson Can't count the times I've said I was going to do this, but I made it up Shepherd's pass a couple times alone and with Warren, not to mention the honest effort on the Northeast Ridge with Brad

Williamson Can't count the times I've said I was going to do this, but I made it up Shepherd's pass a couple times alone and with Warren, not to mention the honest effort on the Northeast Ridge with Brad Tyndall One day winter ascent with Warren who also liked big days in winter.

Tyndall One day winter ascent with Warren who also liked big days in winter. Split Mountain Tried once before I soloed the St. Jean Couloir in winter. Wish I hadn't lost my camera after the ascent!

Split Mountain Tried once before I soloed the St. Jean Couloir in winter. Wish I hadn't lost my camera after the ascent! Middle Palisade I ran the stellar East Face route in 7:28 round trip, which I think due to some strange technicality may be the fastest known time. It's hard to imagine given how fast the 14er records are these days that this wouldn't be hours faster. Nonetheless, a fine day in the mountains on one of the nicest peaks in the high country. Brainerd and Finger Lakes are the gems they're talked up to be.

Middle Palisade I ran the stellar East Face route in 7:28 round trip, which I think due to some strange technicality may be the fastest known time. It's hard to imagine given how fast the 14er records are these days that this wouldn't be hours faster. Nonetheless, a fine day in the mountains on one of the nicest peaks in the high country. Brainerd and Finger Lakes are the gems they're talked up to be. Thunderbolt, Starlight, North Palisade, Polemonium Peak, Mount Sill (with Warren) The Palisades Traverse is still the longest day I've ever had in the mountains, a full 26 hours (2 sunrises in one day!!!). What a spectacular adventure. We didn't summit Sill, but I climbed the North Couloir after graduating undergrad only to break my arm tripping on the trail at First Lake (sorry Dad and Sue!)

Thunderbolt, Starlight, North Palisade, Polemonium Peak, Mount Sill (with Warren) The Palisades Traverse is still the longest day I've ever had in the mountains, a full 26 hours (2 sunrises in one day!!!). What a spectacular adventure. We didn't summit Sill, but I climbed the North Couloir after graduating undergrad only to break my arm tripping on the trail at First Lake (sorry Dad and Sue!)

White Mountain Peak Casually ran this in 2:58 car to car, also a fastest known time. Same as Middle Pal, I'd be shocked if some Yosemite hard man hasn't run this faster.Shasta (Tried a couple times, first with Leor, turned back due to insane winds) Finally got the weather right after my first expedition to Nepal in 2010. I soloed the Casaval Ridge in 27 hours...Stanford to Stanford. Just 11 hours on the route proper. One of my finest days ever in the mountains. Sunrise from the Catwalk was among the best I've ever seen.

White Mountain Peak Casually ran this in 2:58 car to car, also a fastest known time. Same as Middle Pal, I'd be shocked if some Yosemite hard man hasn't run this faster.Shasta (Tried a couple times, first with Leor, turned back due to insane winds) Finally got the weather right after my first expedition to Nepal in 2010. I soloed the Casaval Ridge in 27 hours...Stanford to Stanford. Just 11 hours on the route proper. One of my finest days ever in the mountains. Sunrise from the Catwalk was among the best I've ever seen.

Black Kaweah: Earning an adventure

The wild Kaweahs of the southern Sierra Nevada have long been on my mind. Their reputation for remoteness, lightning strikes, loose rock make even approaching these peaks a challenging and rewarding experience. Jonathan and I set off from the Bay Area for Sequoia National Park's Mineral King late in the evening to miss traffic. By the time we got to the trailhead, it was 2:30 AM and we were delirious. I did my standard bivouac on top of a picnic table, slept like a rock and woke up at 7 to get packing. Fortunately, Jonathan and I were on the same page with our gear...no tent, trail running shoes, and 3oz windbreakers would be our weapons of choice. Offsetting the lightweight clothing, we opted to take a ton of food and a full climbing rope and rack for an shot at the seldom-attempted Kaweah traverse, a notoriously heinous, loose climbing objective. After a long talking to by the rangers, we set off cross country over two high ranges, crossing Glacier Pass and Hands and Knees Pass before dropping down to our bivy spot on Big Arroyo.

The wild Kaweahs of the southern Sierra Nevada have long been on my mind. Their reputation for remoteness, lightning strikes, loose rock make even approaching these peaks a challenging and rewarding experience. Jonathan and I set off from the Bay Area for Sequoia National Park's Mineral King late in the evening to miss traffic. By the time we got to the trailhead, it was 2:30 AM and we were delirious. I did my standard bivouac on top of a picnic table, slept like a rock and woke up at 7 to get packing. Fortunately, Jonathan and I were on the same page with our gear...no tent, trail running shoes, and 3oz windbreakers would be our weapons of choice. Offsetting the lightweight clothing, we opted to take a ton of food and a full climbing rope and rack for an shot at the seldom-attempted Kaweah traverse, a notoriously heinous, loose climbing objective. After a long talking to by the rangers, we set off cross country over two high ranges, crossing Glacier Pass and Hands and Knees Pass before dropping down to our bivy spot on Big Arroyo.

It was a tough day, but Little Five Lakes are as beautiful as they're talked up to be! We got to bed early in order to accommodate a 3AM start up Black Kaweah. From the beginning, I could tell my lack of sleep and nutrition were affecting things. Both of us felt the altitude during the night, but as we ascended above the spectacular tarns en route to Black Kaweah, my altitude symptoms worsened. By the time we were scrambling and soloing the challenging rock high on the peak, I was definitely feeling it. Nonetheless, we reached Black Kaweah's remote and tiny summit and were rewarded with sweeping views of the entire range. We also learned we were the first visitors here since September of last year. Given how remote (probably 20+ miles of mostly cross country travel to reach the peak alone) and challenging the climb, that's not too surprising.

It was a tough day, but Little Five Lakes are as beautiful as they're talked up to be! We got to bed early in order to accommodate a 3AM start up Black Kaweah. From the beginning, I could tell my lack of sleep and nutrition were affecting things. Both of us felt the altitude during the night, but as we ascended above the spectacular tarns en route to Black Kaweah, my altitude symptoms worsened. By the time we were scrambling and soloing the challenging rock high on the peak, I was definitely feeling it. Nonetheless, we reached Black Kaweah's remote and tiny summit and were rewarded with sweeping views of the entire range. We also learned we were the first visitors here since September of last year. Given how remote (probably 20+ miles of mostly cross country travel to reach the peak alone) and challenging the climb, that's not too surprising.

But the ridge looked far too loose and questionable to be fun, so we descended and charged out of the range, crossing the Great Western Divide at Black Rock Pass along the way. Black Kaweah in a weekend was no joke (carrying a 60m rope all the way up it didn't make it any easier), but it's hard to complain with a beautiful, challenging and rewarding experience in sunny California. We got our money's worth!

But the ridge looked far too loose and questionable to be fun, so we descended and charged out of the range, crossing the Great Western Divide at Black Rock Pass along the way. Black Kaweah in a weekend was no joke (carrying a 60m rope all the way up it didn't make it any easier), but it's hard to complain with a beautiful, challenging and rewarding experience in sunny California. We got our money's worth!

Winter traverse of the High Sierra

With all of the recent polar vortex talk, it could be easy to conclude that winter, glaciers and climate as we know it are here to stay. Well, out here in California, my good friend Zach and I just crossed the Sierra Nevada. In sneakers. In two and a half days in the heart of "winter." California, if you haven't heard, is in a ridiculous drought right now.Zach and I were excited at the prospect of this unique trip and a chance to visit some of California's threatened glaciers in winter. Borrowing from the light is right, alpine-style ethic, we stripped down to the bare essentials and rock hopped, plunge-stepped, and slipped along icy trail from the Eastern Sierra to Yosemite Valley.

With all of the recent polar vortex talk, it could be easy to conclude that winter, glaciers and climate as we know it are here to stay. Well, out here in California, my good friend Zach and I just crossed the Sierra Nevada. In sneakers. In two and a half days in the heart of "winter." California, if you haven't heard, is in a ridiculous drought right now.Zach and I were excited at the prospect of this unique trip and a chance to visit some of California's threatened glaciers in winter. Borrowing from the light is right, alpine-style ethic, we stripped down to the bare essentials and rock hopped, plunge-stepped, and slipped along icy trail from the Eastern Sierra to Yosemite Valley.

Thanks to Brad and Matt for dropping us off in style, and Seanan for the unlikely encounter in Yosemite and company on the way home!

Thanks to Brad and Matt for dropping us off in style, and Seanan for the unlikely encounter in Yosemite and company on the way home!

High Sierra Fun

I definitely needed a break after getting back from Nepal, but I was eager to spend a few days out in my beautiful backyard--California's High Sierra. I spent some quality time with my good friend Mike in Yosemite's spectacular high country over July 4th weekend that included top-notch dirtbag camping, homemade fajitas and perfect granite climbs. We spent our first day on Matthes Crest, one of Tuolumne's classic adventures.

I definitely needed a break after getting back from Nepal, but I was eager to spend a few days out in my beautiful backyard--California's High Sierra. I spent some quality time with my good friend Mike in Yosemite's spectacular high country over July 4th weekend that included top-notch dirtbag camping, homemade fajitas and perfect granite climbs. We spent our first day on Matthes Crest, one of Tuolumne's classic adventures.

The next day, we started hiking early to attempt the West Ridge of Mount Conness. We had a challenging approach that went up and nearly to the summit of Conness before dropping down its west face to the base of the route.

The next day, we started hiking early to attempt the West Ridge of Mount Conness. We had a challenging approach that went up and nearly to the summit of Conness before dropping down its west face to the base of the route. As we were ready to rope up, puffy cumulous clouds turned more menacing. After a tiny bit of contemplation, we shouldered our packs and hiked back up and over the peak, unwilling to risk a thunderstorm on an exposed ridge. On the hike back over, I quickly tagged the summit but we'll have to return to try one of Yosemite's best routes. Aside from being a bit of a buffet for the mosquitoes, the trip couldn't have been better.

As we were ready to rope up, puffy cumulous clouds turned more menacing. After a tiny bit of contemplation, we shouldered our packs and hiked back up and over the peak, unwilling to risk a thunderstorm on an exposed ridge. On the hike back over, I quickly tagged the summit but we'll have to return to try one of Yosemite's best routes. Aside from being a bit of a buffet for the mosquitoes, the trip couldn't have been better.

I also had the chance to spend a weekend at Courtright Reservoir on the western side of the Sierra. It was great to get to a part of the range that I've never seen and have been eager to explore for a long time. There was some fun climbing, a hike of Eagle Peak, and swimming in the surprisingly warm reservoir.

I also had the chance to spend a weekend at Courtright Reservoir on the western side of the Sierra. It was great to get to a part of the range that I've never seen and have been eager to explore for a long time. There was some fun climbing, a hike of Eagle Peak, and swimming in the surprisingly warm reservoir.

Late-season Sierra rock

I've taken a few weekend trips to the Sierra before winter truly sets in. First up was Lover's Leap in the Tahoe area with Mike. We've done a fair amount together, and he's really come along as a trad follower and now climbs way harder than I do.

I've taken a few weekend trips to the Sierra before winter truly sets in. First up was Lover's Leap in the Tahoe area with Mike. We've done a fair amount together, and he's really come along as a trad follower and now climbs way harder than I do.

On Saturday, we went up a bunch of Lover's Leap moderate classics on the Hogsback and East Wall. I think Pop Bottle takes the cake as the most fun we had. On Sunday, we did a fair amount of anchor practice before Mike took the sharp end for the first time on Deception. This was also a blast and Mike did a fantastic job on his first trad lead.

On Saturday, we went up a bunch of Lover's Leap moderate classics on the Hogsback and East Wall. I think Pop Bottle takes the cake as the most fun we had. On Sunday, we did a fair amount of anchor practice before Mike took the sharp end for the first time on Deception. This was also a blast and Mike did a fantastic job on his first trad lead. Last weekend, I headed up to Yosemite to take new climbers McKee and Nick on an adventure. We met up with Zach and Emily to toprope on Glacier Point Apron and then climb the Grack.

Last weekend, I headed up to Yosemite to take new climbers McKee and Nick on an adventure. We met up with Zach and Emily to toprope on Glacier Point Apron and then climb the Grack. On Sunday, we awoke and left the Valley early in the morning and started up the icy trail towards Cathedral Peak in Tuolumne. By mid-morning it was warm, but the substantial amount of snow and the expansive views gave the high country a winter feel.

On Sunday, we awoke and left the Valley early in the morning and started up the icy trail towards Cathedral Peak in Tuolumne. By mid-morning it was warm, but the substantial amount of snow and the expansive views gave the high country a winter feel. We roped up covering snow and slabs to the knife-edge ridge between Cathedral and Eichorn Pinnacle. Zach made a nice lead around the corner while I finished the spectacular short route. A wild rappel brought us all back together. We descended during a spectacular sunset and we reached the cars as darkness set in. Thanks everyone for the mountain fun!

We roped up covering snow and slabs to the knife-edge ridge between Cathedral and Eichorn Pinnacle. Zach made a nice lead around the corner while I finished the spectacular short route. A wild rappel brought us all back together. We descended during a spectacular sunset and we reached the cars as darkness set in. Thanks everyone for the mountain fun!